Jewish Leaders – Recognition of the Messiah?

Jewish leadership acknowledged the supernatural abilities and authority of Jesus of Nazareth…some even recognized him as the Messiah yet many eventually sought to kill him. It began at the time of his birth.

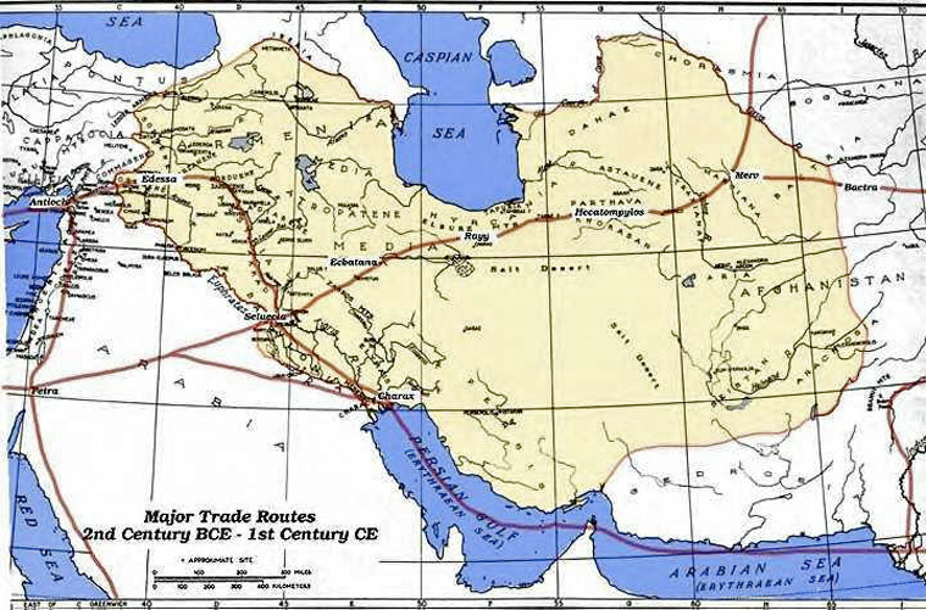

Magi saw signs that a special King of the Jews was to be born and began a quest traveling hundreds of miles not knowing exactly where to find him. Going to the king’s palace in Jerusalem seeking more information, King Herod gave the Magi the birth location of the Messiah as it was provided to him by the Jewish religious experts in the Law and chief priests.

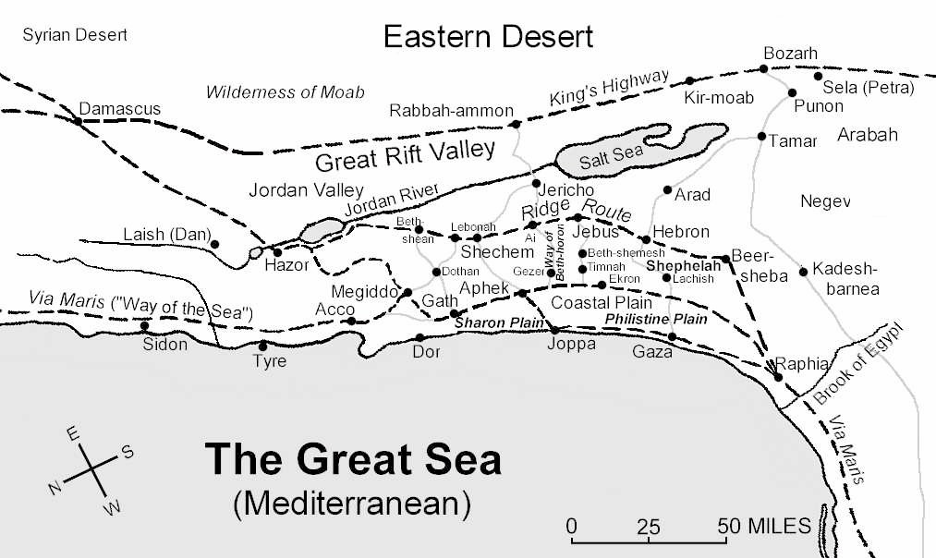

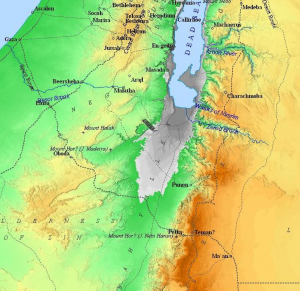

Herod’s question to them had been simple – where is the Christ (Greek for Messiah) to be born? His question was based not on “if,” rather an assumption of fact asking “where” the Messiah was to be born? Their answer: “In Bethlehem of Judea.”[1] Accordingly, based on the response from the Jewish religious experts, Herod sent the Magi to Bethlehem where they did indeed find the child, Jesus.

Eight days after Jesus was born in Bethlehem, Joseph and Mary took him to the Temple in Jerusalem a few miles away to comply with the Jewish laws to formally name him, to be circumcised, offer a sacrifice and for his father to bless him.[2]

A man named Simeon is described in Luke as a righteous and devout man was who was seeking the “consolation of Israel.” He had previously received a vision that he would not die until he had seen the Messiah.

Simeon was inspired to go to the Temple on a particular day which happened to be the same time that Joseph and Mary took baby Jesus to the Temple. He met Joseph and Mary at the Temple, took the babe in his arms, blessed Jesus and said:

LK 2:30-32 “For my eyes have seen your salvation, which you have prepared in the sight of all people, a light for revelation to the Gentiles and for glory to your people Israel.” (NIV)

Amazed by Simeon’s words, he had one more thing to tell Joseph and Mary about their child. Simeon foretold to them what to expect for the life of Jesus:

LK 2:34-35 “This child is destined to cause the falling and rising of many in Israel, and to be a sign that will be spoken against, so that the thoughts of many hearts will be revealed. And a sword will pierce your own soul too.” (NIV)

Anna was a prophetess, the daughter of Phanuel of the Asher tribe. Her husband had died after only seven years of marriage leaving her a widow for the next 84 years. Living a reclusive life, she never left the Temple fasting and praying day and night.[3]

Seeing Joseph, Mary and Jesus during their visit to the Temple, Anna came up to them and began giving thanks to God. After that time, the prophetess spoke of Jesus to all who came into the Temple interested in the “redemption of Jerusalem.”

Several groups of Jewish religious leaders are referenced in the Gospels typically in opposition to Jesus during his final three-year ministry – the rulers of the Sanhedrin, the High Priest, the Pharisees, the Herodians, the chief priests, the legal experts and the elders.

Opposing Jesus as a threat to fundamental Judaism, the Jewish leaders acknowledged the supernatural abilities and powers of Jesus through their criticisms thereby inadvertently corroborating that he possessed the characteristics of the prophesied Messiah.[4]

Sanhedrin was the ruling political body of the Jewish theocracy originally established by Moses.[5] The High Priest was the head of the Sanhedrin and political leader of all the Jewish people.[6]

Scribes were the legal experts of Jewish law, the lawyers of the day.[7] Chief priests were religious leaders from the Temple and members of the Sanhedrin.[8] Elders were valued in Jewish society for their wisdom in consultations.[9] Herodians were a minor religious faction although they shared a common enemy of Jesus.[10]

Chief priests, legal experts and elders acknowledged Jesus had the supernatural power and authority to cast out demons and to perform “signs” often translated as “miracles.”[11] Asking Jesus to identify the authority of his power “to do these things,” they could not answer a legal riddle he posed to them and, in return, Jesus didn’t answer their question either.[12]

Pharisees were one of three predominate religious factions in Jerusalem and most noticeable throughout Judea and were the primary nemesis of Jesus in the Gospels.[13] Inexplicably, they viewed Jesus as being on their level calling him “teacher” who taught “the way of God in truth” and took offense when Jesus dared to eat with the “sinners.”[14] Admitting Jesus performed “signs ” so amazing that “the whole world has gone after him,” it served as the trigger point to take action to kill him.[15]

Arresting Jesus, the Jewish leadership put him on trial when he admitted under oath to being the “Son of God.” The High Priest in charge of the trial, Caiaphas, reacted to the admission by tearing his clothes in a customary display of grief for hearing blasphemy exclaiming, “Why do we still need witnesses?”[16]

Not all the Jewish leadership shared the same disdainful views of Jesus. In one instance, Jesus was invited to dinner by a Pharisee named Simon.[17] While dining, an uninvited guest – a local woman “sinner” – washed the feet of Jesus with her tears and hair. Jesus forgave her many sins causing Simon and his guests to wonder who is Jesus to be able to forgive sins?[18]

Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea were identified as Jewish rulers who followed Jesus.[19] Nicodemus had met secretly with Jesus and once pushed back on unfair accusations of his ruling peers.[20] Joseph asked Pilate for the crucified body of Jesus and both Jewish rulers together buried him in Joseph’s unused tomb.[21]

King Herod believed as a result of the Magi’s visit through the words of his royal Jewish council that the Messiah had been born in Bethlehem. At the Temple, baby Jesus was recognized twice as the Messiah. Later in life, archenemies of Jesus acknowledged his supernatural abilities to heal, perform other miracles, and his authority of power over evil.

What did some Jewish leaders see that others did not – was Jesus the prophesied Messiah?

Updated May 6, 2024.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

REFERENCES:

[1] Matthew 2:5.

[2] Luke 2:21-33.

[3] Luke 2:36-38.

[4] Exodus 18:25-26; Deuteronomy 1:15-17, 16:18-20; Matthew 12:9; Mark 11:18; Luke 6:6-11; John 11:46-48. Sanhedrin 49b. Soncino Babylonian Talmud. 1935-1948. <https://israelect.com/Come-and-Hear/sanhedrin/sanhedrin_49.html “Chief Priests.” Encyclopedia.com. 2019. <https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/chief-priests>

[5] “Sanhedrin.” JewishEncyclopedia.com. 2011. <https://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/12291-portalis-comte-joseph-marie>

[6] “High Priest.” JewishEncyclopedia.com. 2011. <https://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/7689-high-priest>

[7] “Scribes.” JewishEncyclopedia.com. 2011. <https://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/13831-sofer>

[8] “Chief Priests.” Encyclopedia.com. 2019. <https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/chief-priests>

[9]“Elder.” Jewish Virtual Library. 2021. <https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/elder>

[10] “Herodians.” JewishEncyclopedia.com. 2011. <https://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/7605-herodians>

[11] Mark 2:6; 3:22; Luke 6:7; John 11:47.

[13] “Pharisees.” JewishEncyclopedia.com. 2011. <https://jewishencyclopedia.com/articl s/12050-perushim >

[14] Matthew 22:16; Mark 2:13-16. Luke 5:30, 7:39, 15:2: John 8:3.

[15] Matthew 12:9, 22:15; Mark 3:1-6; Luke 5:21, 6:2, 11, 11:53; John 7:31-32, 11:47-50; 12:19.

[16] Mark 14:61-63. NET, NRSV. CR Matthew 26:63-65; Luke 22:70-71. O’Neal, Sam. Learn Religions. 2019. <https://www.learnreligions.com/why-people-in-the-bible-tore-their-clothes-363391>

[17] Luke 7:44.

[18] Luke 7:36-35.

[19] John 3:1, 7:50-51, 19:38-39.

[20] John 7:50-51.

[21] Matthew 27:57-60; Mark 15:42-46; Luke 23:50-53; John 19:38-42.