Arabian Desert – Two Routes to Bethlehem?

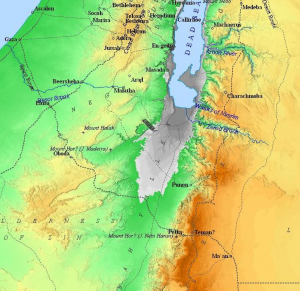

Matthew’s Nativity account of the wise men, the Magi, describes their quest to find the newborn King of the Jews first took them to Jerusalem, then on to Bethlehem. Persia-to-Judea travel had one formidable obstacle – the great Arabian Desert – one of the largest, if not the largest desert, in the world.[1]

Erza 7:9 mentions how a similar journey from Babylon to Jerusalem took four months. Ezra was written after the Hebrew’s release from Babylonian captivity though still under the rule of the Persian Empire in the late 300 BC era.[2]

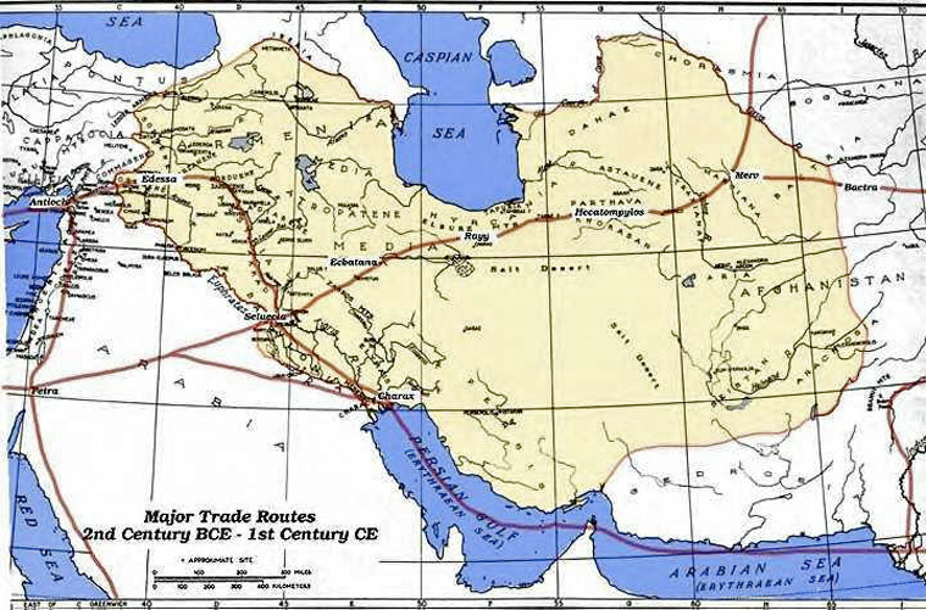

Scrolling forward to the last quarter of the 200s BC, trade routes had been established by the Parthian Empire making travel relatively much faster.[3] Commonly referred to as “caravan routes,” they were the busy interstate highways of the day.

Dotted with trading posts, they were the best practical means for land travel. Especially true considering the foreboding Arabian Desert.[4]

Shortest, easiest and safest travel option to Judea was the established trade route around the northern edges of the Arabian Desert. Known as the northern Parthian loop, it could be used for travel from Persia to Jerusalem.

From Seleucia near present day Baghdad, then to Jerusalem was approximately 700 miles.[5]

Coursing north through the populous area east of the Euphrates River, the route went to Edessa in southeast Turkey; turned west to Damascus, Syria; then turned south following the ancient King’s Highway paralleling the east side of the Jordan River.

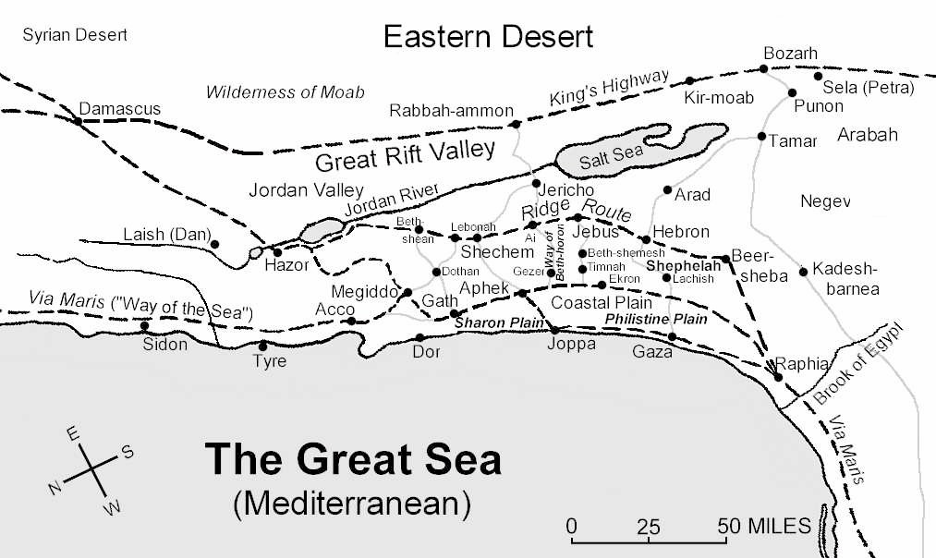

Magi wanted to start in Jerusalem to seek guidance from ruler of the land of Judea, King Herod. Trade route spurs going west to Jerusalem off the King’s Highway across the Jordan River were limited to only three.

Traveling from the north, the first two spur routes were not logical choices for a Jerusalem destination. The third and last route option headed west by fording the Jordan going by Jericho just above the Dead Sea.

Jericho was also the location of King Herod’s winter palace where he would soon travel during his final days.[6] Crossing of the Jordan near Jericho was the same place where the Hebrews entered into the land of Abraham after their wonderings in the Sinai wilderness.[7]

Jerusalem was not located on the common caravan routes making arrival of the Magi in the city a newsworthy event and everyone seemed to be aware of it.[8] Attention may also have been drawn to their conspicuous caravan of camels; their foreign grandiose attire; or perhaps that they were even regarded as kings from Persia.[9]

Magi were well-known by reputation for their origins in Persia east of Judea hundreds of miles away. Famed thirteenth century explorer, Marco Polo, wrote in 1298 of his travels to the Province of Persia searching for information about the Magi.[10]

Polo discovered the Magi were also called “fire-worshippers,” a name for the Magi in the Talmud.[11] He learned they were from a city called Saba, about 50 miles southwest of Tehran, Iran.[12]

Matthew’s account neither discloses the number of magi nor that they were kings. Nevertheless, Marco Polo identified the Magi as three kings from Dyava, Saba and the castle of Palasata who presented “three offerings” to the baby.[13]

It is obvious the Magi were recognized on the highest social hierarchy when King Herod granted the Magi immediate access to his palace. After consulting with Jewish religious experts and a deal with the Magi, Herod directed them to go to Bethlehem located only 5 miles to the south of Jerusalem.

MT 2:16 “When Herod realized that he had been outwitted by the Magi, he was furious…”(NIV)

After being warned not to return home the way they came, the Magi took a different route back to their homeland – was there a second route?

Herod would assuredly know they were in Jerusalem if returning home the way they came. If the Magi went around the city, they would still have to go by Jericho where undoubtedly area look-outs would certainly inform the King.

Herod would assuredly know they were in Jerusalem if returning home the way they came. If the Magi went around the city, they would still have to go by Jericho where undoubtedly area look-outs would certainly inform the King.

Another return route was possible although it was longer – the southern Parthian loop via Petra.

Literally at the doorstep of the Magi in Bethlehem, the southern Parthian trade route avoided going through Jerusalem or by Jericho.

Routing south out of Bethlehem to Hebron was the Central Ridge, south of the Dead (Salt) Sea connecting to the Spice Route, the route ran to the King’s Highway and on to Petra. From Petra, the southern Parthian route went across the Arabian Desert to central Persia.[14]

Other less traveled minor route spurs off the Central Ridge Road had trade-offs. While these routes may have shortened the southward path, they were probably more difficult passages with fewer trading posts and greater risks such as robbers, water supply, etc.

Do these Southern secondary trade routes options corroborate and add credibility to the Gospel account of Matthew and the Nativity of Jesus of Nazareth?

Updated November 17, 2024.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

REFERENCES:

[1] Matthew 2:1, 12. “Arabian Desert.” New World Encyclopedia. n.d. <https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Arabian_Desert> “Arabian Desert.” Encyclopædia Britannica. 2020. <https://www.britannica.com/place/Arabian-Desert>

[2] “Ezra and Nehemiah, Books of.” Jewish Virtual Library. 2020. <https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/ezra-and-nehemiah-books-of> “Ezra.” Encyclopædia Britannica. 2020. <https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ezra-Hebrew-religious-leader>

[3] “Trade between the Romans and the Empires of Asia.” MetMuseum.org. 2020. <https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/silk/hd_silk.htm> “Map of Roman & Parthian Trade Routes.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. 2020. <https://www.ancient.eu/image/11763/map-of-roman–parthian-trade-routes> Hopkins, Edward C. D. “History of Parthia.” Parthia.com. 2008. <http://www.parthia.com/parthia_history.htm> “Parthian Empire.” Iran Chamber Society. 2020. <http://www.iranchamber.com/history/parthians/parthians.php>

[4] Stillwell, Richard, et. al. “Bernice or Pernicide Portum (Madinet el-Haras) Egypt.” The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. n.d. <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0006:entry=berenice-1&highlight=caravan> Stillwell, Richard, et. al. “Beroea (Aleppo) Syria.” The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. n.d. <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0006:entry=beroea&highlight=caravan> Stillwell, Richard, et. al. “Dura Europos Syria.” The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. n.d. <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0006:entry=dura-europos&highlight=caravan> Stillwell, Richard, et. al. “Palmyra (Tadmor) Syria.” The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. n.d. <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0006:entry=palmyra&highlight=caravan> “Trade Routes/” National Museum of American History. n.d. <https://web.archive.org/web/20160618154742/http://americanhistory.si.edu/numismatics/parthia/frames/pamaec.htm> “Chapter 4. Iran Historical Maps Arsacid Parthian Empire, Armenian Kingdom.” “Iran Historical Maps Arsacid Parthian Empire, Armenian Kingdom.” Iran Politics Club. n.d. <http://iranpoliticsclub.net/maps/maps04/index.htm> “Roads in Israel – 1st Century AD.” Bible-History.com. Map. n.d. <https://www.bible-history.com/maps/first-century-roads-israel2.jpg>

[5] II Kings 25:1-17; Jeremiah 52:3-30. Middle East. Bing.com. Map. 2020. <https://www.bing.com/maps?osid=a2a3d404-6095-4abc-9ac8-b6d695d42293&cp=34.13455~41.097873&lvl=7&v=2&sV=2&form=S00027> “Atlas of Iran Maps.” IranPoliticsClub.net. Chapter 4. March, 2000. <http://www.iranpoliticsclub.net/maps/maps04/index.htm> “Spice Ways.” Israel Antiquities Authority. Map. n.d. 2014. <http://www.mnemotrix.com/avdat/spiceroute2.gif> “Trade Routes of Palestine.” Bible Odyssey. Map. 2019. <https://www.bibleodyssey.org/en/tools/map-gallery/v/map-trade_routes-g-01>

[6] Josephus, Flavius. Antiquities of the Jews. Trans. and commentary. William Whitson. The Complete Works of Josephus. 1850. Book XVII. Chapter VI. <http://books.google.com/books?id=e0dAAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false> Geva, Hillel. “Archaeology in Israel: Jericho – The Winter Palace of King Herod.” Jewish Virtual Library. 2020. <https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jericho-the-winter-palace-of-king-herod> “Herodian Jericho.” Oxford Bible Studies Online. 2020. <http://www.

[7] Numbers 20:19, 22:1; Deuteronomy 32:48, 34:1-4; Joshua 3:14-17. “Roads in Israel.” Bible History Online. Map. n.d. <http://www.bible-history.com/maps/ancient-roads-in-israel.html>oxfordbiblicalstudies.com/article/opr/t393/e57>

[8] Matthew 2:3.

[9] Strabo. Geography. Chapters II-III. n.d. <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0239:book=1:chapter=2&highlight=magi> <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0239:book=15:chapter=3&highlight=magi> Diogenes Laertius. Lives of Eminent Philosophers. n.d. <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0258:book=1:chapter=prologue&highlight=magi> Stillwell, Richard et. al. “Gaza Israel.” The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. n.d. <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0006:entry=gaza&highlight=caravan>

[10] Polo, Marco. The Travels of Marco Polo the Venetian. 1818. Ed. Ernest Rhys. 1908 Edition. Chapter XI. p 50. <http://archive.org/stream/marcopolo00polouoft#page/50/mode/2up> “Marco Polo.” Bibliography.com. 2020 <https://www.biography.com/explorer/marco-polo> “Marco Polo and his travels.” Silk-Road.com. n.d. <http://www.silk-road.com/artl/marcopolo.shtml>

[11] Soncino Babylonian Talmud. Ed. Isidore Epstein. The Soncino Press. 1935-1948. Sanhedrin 98a. <https://israelect.com/Come-and-Hear/sanhedrin/sanhedrin_98.html#98a_22> Sanhedrin 74b. <https://israelect.com/Come-and-Hear/sanhedrin/sanhedrin_74.html> “Babylonia.” Jewish Encyclopedia. 2011. <http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/10263-magi>

[12] Saveh, Iran (untitled). Bing.com/maps. Map. 2020. <https://www.bing.com/maps?osid=caeb94c6-d007-42ed-a5c8-19628ce0cebc&cp=35.411126~50.908664&lvl=9&v=2&sV=2&form=S00027> Hartinger, J. A. “Saba and Sabeans.” Catholic Encyclopedia. Volume 13. 1912. NewAdvent.org. 2009. <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/13285c.htm> Strabo. Geography. Chapter III. n.d. <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0239:book=15:chapter=3&highlight=magi>Stillwell, Richard, et. al. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. “Hatra Iraq.” n.d. <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0006:entry=hatra&highlight=caravan>

[13] Matthew 2:11.

[14] Josephus, Flavius. Wars of the Jews. Trans. and commentary. William Whitson. The Complete Works of Josephus. 1850. 4.451. <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0148:book=4:section=451&highlight=petra>“Major Trade Routes.” Bibarch.com. Map. n.d. <http://www.bibarch.com/images/Map-Regions.jpg> Ancient Israel trade routes (untitled). BibleWalks.com. Map. 2011. <https://web.archive.org/web/20190414151021/https://biblewalks.com/Photos72/IncenseRoute.JPG> “Ancient Palestine.” The History of Israel. Map. n.d. <http://www.israel-a-history-of.com/images/AncientRoadsandCities2.jpg> “Old Testament Map & History.” The History of Israel. “Ancient Palestine.” Map. n.d. <http://www.israel-a-history-of.com/old-testament-map.html> ; “Spice Ways.” Israel Antiquities Authority. Map. n.d. Mnemotrix Systems, Inc. 2014. <http://www.mnemotrix.com/avdat/spiceroute2.gif> “The Urantia Papers’ First Century Palestine.” The Urantia Book Fellowship. Map. n.d. 2013. <http://web.archive.org/web/20070820230158/http://www.urantiabook.org/graphics/gifmap1.htm> “Eastern Desert.” Pinterest.com. Map. n.d. <https://i.pinimg.com/originals/cb/8e/5c/cb8e5cdfa8e96c2fdc1eb3c884cc5f75.jpg> Last accessed 19 Dec. 2021. Stillwell, Richard, et. al. “Petra (Selah) Jordan.” The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. n.d. <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0006:entry=petra-2&highlight=caravan> Stillwell, Richard, et. al. “Elusa (El-Khalasa) Israel.” The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites.. n.d. <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0006:entry=elusa-2&highlight=caravan>

Luke’s Nativity account identifies two Roman rulers not found in Matthew. Serving as additional historical date markers to King Herod, it adds

Luke’s Nativity account identifies two Roman rulers not found in Matthew. Serving as additional historical date markers to King Herod, it adds