Astronomy Tales: the Birth & Crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth

“Follow the science” can be applied to astronomy using NASA data. No mystical meaning is found in astronomy where positions of stars and planets follow a predictive path that can be charted past, present and future.[1]

Planets move in a rotation path around the Sun whereas stars are stationary. Both can appear in different places in the sky based on such variables as nightly diurnal motions, planetary rotations, seasons and earthly viewing location.

God Himself pointed out the absoluteness of astronomy when He promised the Messiah would sit on the throne of David:

Jer. 33:20-21 “Thus says the LORD: If any of you could break my covenant with the day and my covenant with the night, so that day and night would not come at their appointed time, only then could my covenant with my servant David be broken, so that he would not have a son to reign on his throne…” (NRSV)

Astrology, different from astronomy, is the belief that celestial bodies influence a person’s journey in life, but astrology is not a “science.”[2] Horoscopes, for example, are an attempt to define a personality, successes, sorrows, challenges – a life’s destiny.

Various cultures have given names to planet-stars and fixed stars; assigned them to zodiacs; and even going so far as to worship them as gods. Going back millennia, many have attempted to interpret the meaning of the various cosmic alignments – Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Greeks, Romans and even Jews.[3]

Persian Zoroastrian teachings of the Magi espoused that every planet has a significance.[4] Some have viewed interactions of the heavenly bodies and alignments as signs with earthly significance indicating something is about to happen or has occurred.[5]

BIRTH OF JESUS OF NAZARETH

Magi in Matthew’s account were not motivated by an ancient prophecy or a prophet, an angelic appearance, or any type of divine revelation. Instead, their actions were compelled by an awe-inspiring scene they observed in the night sky.

Magi confidently believed in the sign when they saw “his star” compelling them to do several things well-beyond normal. They set out on a risky months-long journey around the great Arabian Desert to a foreign land in Judea not knowing where their quest would end; sought input from a ruthless Judean king, eventually even defying him; brought expensive gifts for this unknown baby; and they planned to worship him.[6]

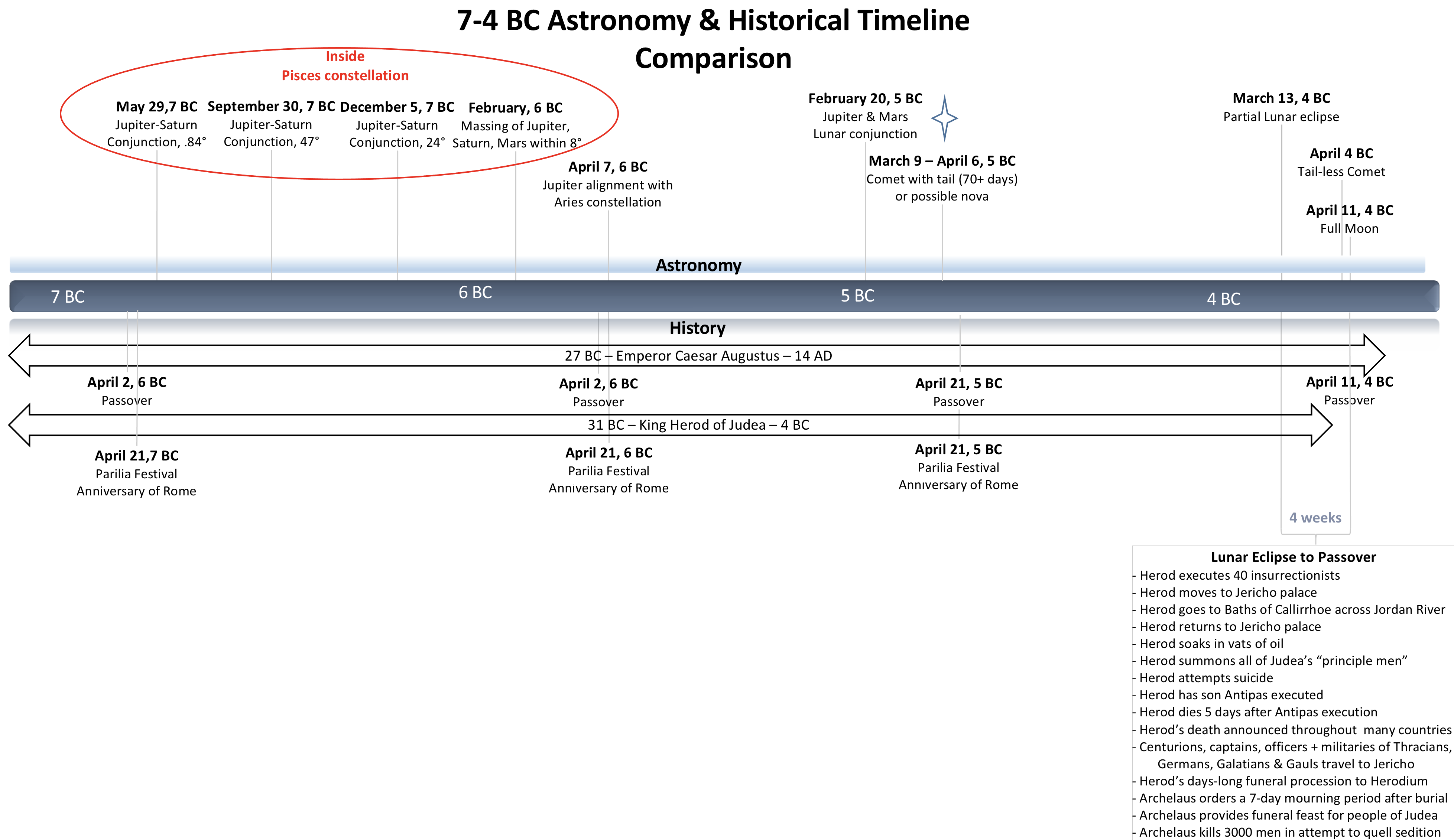

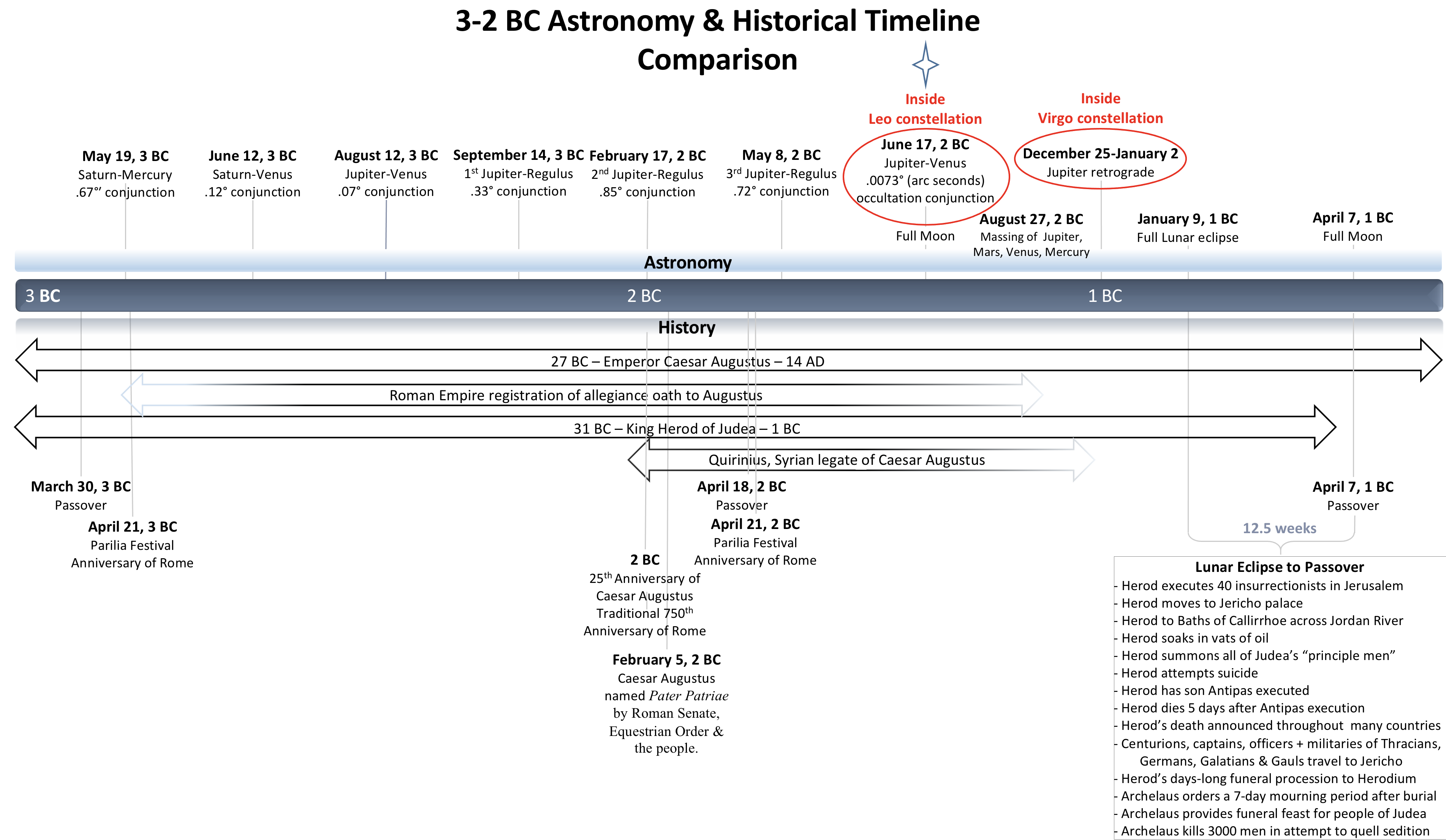

NASA’s astronomy data reveals that closing out the last 7 years of the BC era, two sets of stellar events occurred during the years 7-5 BC and 3-1 BC. Rare conjunctions, movements and alignments typically occurring centuries apart, transpired in a very short period of time.

One common fact to Matthew and Luke: King Herod was alive when Jesus was born while secular history which focuses primarily on the death date of Herod.[7] Matthew reported the death of King Herod to end the Nativity account.

Many have used the 7-5 BC timeline with a partial lunar eclipse to support the secular year of Herod’s death in 4 BC. Historian Josephus described in detail events surrounding Herod’s death between a lunar eclipse and the Passover leading to research that points to the King’s death in 1 BC when a full lunar eclipse occurred.

A four-prong approach overlaying secular history accounts, Jewish calendars, the science of astronomy data and Gospel accounts produces two fascinating scenarios for the birth of Jesus and the death of Herod. If the Magi acted on either scenario, which one makes the most logical sense?

CRUCIFIXION OF JESUS OF NAZARETH

Astronomy data compared with historical accounts and the Gospels, can be used as a basis for determining the crucifixion date Jesus of Nazareth. Three sets of information – astronomy data, history, Gospels – are defined separately below and then triangulated together to form one likely possibility.

Astronomy

NASA astronomy data serves as an accurate method to determine the Passover dates as an alternative to unreliable calendars of antiquity. (Calendar conversions to Julian, Gregorian and Jewish calendars are unreliable.)[8]

Jewish Nissan 15th, Passover, always occurs on the first full moon after the vernal equinox typically believed to be March 21st although that date varies scientifically by as much as two days based on Naval Observatory and NASA data.[9] Full moon dates within these scientific parameters for the years 28-33 AD are:[10]

28 AD: March 29 (Monday) 31 AD: March 27 (Tuesday)

29 AD: April 17 (Sunday) 32 AD: April 14 (Monday)

30 AD: April 6 (Thursday) 33 AD: April 3 (Friday)

Often cited for the crucifixion scenario is a solar eclipse to explain the reference in Luke to darkness from noon until three o’clock.[11] NASA astronomy defines when a solar and a lunar eclipse can occur:

“An eclipse of the Sun can occur only at New Moon, while an eclipse of the Moon can occur only at Full Moon” – NASA astronomy [12]

A lunar eclipse is not visible during daylight hours even if one occurred that night.[13] Darkening of the Sun cannot be explained by NASA with data showing only two solar eclipses occurred over Jerusalem – 29 and 33 AD, but not at a Passover.[14]

History – Roman and Jewish:

“At the death of Herod, Augustus Caesar divided his territories among his sons — Archelaüs, Philip, and Herodes Antipas…” making them Tetrarchs.[15] Josephus stated Philip ruled for 37 years meaning he either died in 33 or 36 AD.[16]

Tiberius Caesar began his rule as Roman Emperor on August 19, 14 AD, upon the death of Augustus Caesar. Tiberius ruled until his own death on March 16, 37 AD, when Caligula (Caius) became Emperor.[17]

Tiberius appointed only two procurators to Judea, first Valerius Gratus for the years 15-25 AD and secondly, Pontius Pilate for 10 years from 26-36 AD.[18] Vitellius sent Pilate to Rome in 36 AD to answer to Tiberius for killing Samaritans effectively ending Pilate’s tenure.[19]

Ananus was first High Priest of his family, followed by five of his sons and a son-in-law named Caiaphas.[20] Beginning his 10-year tenure in 26 AD, Caiaphas was the high priest until he was removed by Vitellius during a Passover in 36 AD, the same year he removed Pilate as Procurator.[21]

Tetrarch Antipas met Tetrarch Philip and his wife, Herodias, during a trip to Rome. Antipas and Herodias devised a plan to divorce their current spouses and remarry each other setting in motion a chain reaction of historical events – the execution of John the Baptist; an Arab-Jewish war; and Caesar wanting the demise of an Arab King.[22]

Antipas and Herodias married in 33 AD according to the Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities.[23] Antipas’ first wife, daughter of Arab King Aretas, unbeknownst to Antipas found out about her husband’s divorce scheme with Herodias and made arrangements to return to her father.

John the Baptist, renowned by both Judaism and Islam in addition to Christianity, publicly criticized the illicit, incestuous marital arrangement infuriating Herodias.[24] From the perspective of Josephus, Antipas executed John the Baptist for political reasons.[25]

Aretas and Antipas were agitated to war, according to Josephus, “when all of Herod’s army was destroyed by the treachery of some fugitives, who, though they were of the tetrarchy of Philip, joined with Aretas’s army” – Philip was alive.[27] Secular historians date the Aretas-Antipas war to 36 AD.

Antipas wrote to Tiberius about his defeat to Aretas angering Caesar who ordered his Roman Syrian legate, Vitellius, to capture Aretas or “kill him and, and send him his head.”[28] Tiberius soon died thereafter in 37 AD whereupon Vitellius rescinded the order and sent his military home.[29]

Philip’s tetrarchy became available when he died and Roman Emperor Caligula gave the tetrachy governance position to Agrippa in 37 AD.[30]

Gospels:

Luke 3:1 “In the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius Caesar, when Pontius Pilate was governor of Judea, and Herod was tetrarch of Galilee, and his brother Philip was tetrarch of the region of Iturea and Trachonitis, and Lysanias was tetrarch of Abilene, during the high priesthood of Annas and Caiaphas, the word of God came to John the son of Zechariah in the wilderness.”(NET)[31]

John the Baptist and Jesus began their ministries about the same time. Unlike the three synoptic Gospel accounts of Matthew, Mark and Luke, the Gospel account of John is essentially written in chronological order.

After his baptism by John the Baptist, the Gospel of John chronicled actions taken by Jesus of Nazareth. After being rejected in Nazareth, he moved to Capernaum; chose some of his Disciples in Galilee; attended a wedding in Cana; returned to Capernaum; then traveled to Jerusalem for the first Passover of his ministry.[32]

Approaching the second Passover during his ministry, John “was the burning and shining lamp,” according to Jesus; the past-tense suggesting the ministry of John the Baptist over.[33] Herod Antipas had John the Baptist arrested, but not immediately executed, for publicly criticizing his illicit marital arrangement with Herodias.[34]

Between the second and third Passovers attended by Jesus, people referred to John the Baptist in the past tense. This past-tense usage suggests John the Baptist is no longer alive.[35]

As a reward for a dance performed by his step-daughter (daughter of Philip, identified as Salome by Josephus), Herod Antipas promised anything she wanted.[36] After consulting with her mother, John the Baptist was beheaded at the behest of Herodias.[37]

Triangulation:

John the Baptist began his ministry during the 15th year of Tiberius’ reign. Adding 15 years to the beginning the rule of Tiberius in 14 AD equates to 29 AD.

Jesus of Nazareth did not begin his 3-year ministry until after he was baptized by John the Baptist. This alone eliminates the possibility for the crucifixion year of 29 AD.

Historical accounts from 33-37 AD combined with Biblical accounts support the death of John the Baptist in 32 or 33 AD… Jesus had not yet been executed.

Jesus attended three Passovers in Jerusalem. The third and final Passover ended with his capture, trial and crucifixion.

Sending troops in 36 AD to aide Aretas in a war against Antipas, Philip could not have died in 33 AD. Since Philip ruled for 37 years, it means King Herod could not have died in 4 BC.

Caligula gave the tetrachy of Philip to Agrippa in 37 AD. (It is highly unlikely the governorship of a tetrarchy would have been left unfilled for 3-4 years if Philip had died in 33 AD.)

A requirement for Passover is a full moon and NASA data reveals only one full moon occurred on a Friday.

Triangulating history with astronomy, Gospel accounts and Passover, only one NASA date aligns with all these facts – Friday, April 3, 3AD.

What are the odds that astronomy, supported by secular history and the Gospels, accurately points to both the birth and crucifixion dates of Jesus?

Updated July 6, 2025.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

REFERENCES:

[1] “astronomy.” Merriam-Webster. 2018. <https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/astronomy> “astronomy.” Encyclopædia Britannica. 2022. <https://www.britannica.com/science/astronomy> Redd, Nola Taylor. Space.com. 2017. <https://www.space.com/16014-astronomy.html>

[2] “astrology.” Merriam-Webster. 2022. <https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/astrology> “astrology.” Encyclopædia Britannica. 2018. <https://www.britannica.com/topic/astrology>

[3] Eduljee, K. E. “Zoroastrian-Persian Influence on Greek Philosophy and Sciences.” Zoroastrian Heritage. 2011. <http://zoroastrianheritage.blogspot.com/2011/04/zoroastrian-influence-on-greek.html> Eduljee, K. E. “Astrology & Zoroastrianism,” Zoroastrian Heritage. 2011. <http://zoroastrianheritage.blogspot.com/2011/04/astrology-zoroastrianism.html> Hochhalter, Howard. The Hollow 4 Kids. “A Celestial Road to Truth.” 2022. <https://thehollow4kids.com/a-celestial-road-to-truth/?fbclid=IwAR26hEnI1VfkjcBSRDJp2iyPIaNwPwrDZ0oHYg-pt9V0lumQTxX9WfXk4D0>

[4] Eduljee, K. E. “Is Zoroastrianism a Religion, Philosophy, Way-of-Life…? The Spirit.” Zoroastrian Heritage. 2011. <http://zoroastrianheritage.blogspot.com/2011/05/is-zoroastrianism-religion-philosophy.html> Eduljee, K. E. “Introduction. Zoroastrianism & Astrology.” n.d. <http://zoroastrianastrology.blogspot.com/> “Every Planet Has a Meaning.” Magi Society. Lesson 3. 2008. <http://www.magiastrology.com/lesson1.html>

[5] Matthew 12:39; 16:4; John 3:2; 20:30; Acts 2:22. Quran Surah 3:41; 19:10. <http://search-the-quran.com/search/Yahya> “signs.” Oxford Learners Dictionaries. 2022. <https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/us/definition/english/sign_1?q=signs>

[6] Eduljee, K. E. “Greek Perceptions of Zoroaster, Zoroastrianism & the Magi.” #2, #33. Zoroastrian Heritage. 2011. <http://zoroastrianheritage.blogspot.com/2011/04/greek-perceptions-of-zoroaster.html> “Magi Astronomy.” Magi Society. 2008. <http://www.magiastrology.com/lesson3.html> Humphreys, Colin J. “The Star of Bethlehem – a Comet in 5 BC – And the Date and Birth of Christ.” pp 390-391. SAO/NASA Astrophysics Data System (ADS). 1991. <http://adsbit.harvard.edu//full/1991QJRAS..32..389H/0000391.000.html> Dickinson, David. “Is This Month’s Jupiter-Venus Pair Really a Star of Bethlehem Stand In?” Universe Today. October 14, 2015. <https://www.universetoday.com/122738/is-this-months-jupiter-venus-pair-really-a-star-of-bethlehem-stand-in/> Roberts, Courtney. The Star of the Magi: The Mystery That Heralded the Coming of Christ. pp. 70-71. <https://books.google.com/books?id=480FI6lj3UkC&pg=PA145&lpg=PA145&dq=magi+signs+in+the+sky&source=bl&ots=wQlvIonSLe&sig=yX-toR4CMY1JnebNxQjvYVpHHnc&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj9vsaQlonfAhUInKwKHYG5D144FBDoATABegQICBAB#v=onepage&q=magi&f=false> Hochhalter, Howard. “The Star of Kings and the Magi.” March 21, 2023. video. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KGTmwuqznec>

[7] Mathew 2:1-10; Luke 1:5. Jachowski, Raymond. Academa.Edu. “The Death of Herod the Great and the Latin Josephus: Re-Examining the Twenty-Second Year of Tiberius.” n.d. <https://www.academia.edu/19833193/The_Death_of_Herod_the_Great_and_the_Latin_Josephus_Re_Examining_the_Twenty_Second_Year_of_Tiberius> Steinmann, Andrew E.; Young, Rodger C. Academia.Edu. “Elapsed Times for Herod the Great in Josephus.” 2023. <https://www.academia.edu/39731184/Elapsed_Times_for_Herod_the_Great_in_Josephus?email_work_card=thumbnail>

[8] Beattie, M. J. Church of God Study Forum. “Hebrew Calendar.” n.d. <http://www.cgsf.org/dbeattie/calendar> Richards, E. G. “Explanatory Supplement to the Astronomical Almanac.” 2021. <https://aa.usno.navy.mil/downloads/c15_usb_online.pdf> “Easter Sunday/Jewish Passover Calculator.” WebSpace Science. JavaScript calculator. n.d. <https://webspace.science.uu.nl/~gent0113/easter/easter_text2a.htm> “Jewish holiday calendars & Hebrew date converter.” Hebcal. n.d. <https://www.hebcal.com/converter?hd=16&hm=Nisan&hy=3793&h2g=1> “Hebrew Calendar Converter.” Calculators. 2022. <https://calcuworld.com/calendar-calculators/hebrew-calendar-converter> April 33 AD. TimeandDate.com. calendar. <https://www.messianic-torah-truth-seeker.org/AD-33-3793/PDF-AD-33-3793.pdf>

[9] Leviticus 23:4-7; Numbers 28:16-25. Richards. “Explanatory Supplement to the Astronomical Almanac.” “The Scientific Method by Science Made Simple.” Moss, Aron. “Why Is Passover on a Full Moon?” Chabad.org. <https://www.chabad.org/holidays/passover/pesach_cdo/aid/4250850/jewish/Why-Is-Passover-on-a-Full-Moon.htm> Bikos, Konstantin. “The Jewish Calendar.” TimeAndDate.com. n.d. <https://www.timeanddate.com/calendar/jewish-calendar.html> Cohen, Michael M. “Passover, full moon and fulfillment.” The Jerusalem Post. 2019. <https://www.jpost.com/Israel-News/Culture/Passover-The-full-moon-and-fulfillment-586511> “Determining the Dates for Easter and Passover.” RayFowler.org. n.d. <http://www.rayfowler.org/writings/articles/determining-the-dates-for-easter-and-passover> Beattie. “Hebrew Calendar.” Fairchild, Mary. Learn Religions. “What Is the Paschal Full Moon?. n.d. <https://www.learnreligions.com/paschal-full-moon-700617> “Lunar Eclipses from 0001 to 0100 Jerusalem, ISRAEL” National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Javascrip 2007. <https://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/JLEX/JLEX-AS.html>

[10] Espenak, Fred. “Phases of the Moon: 0001 to 0100 Universal Time (UT).” Astropixels.com. n.d. <http://astropixels.com/ephemeris/phasescat/phases0001.html> “Spring Phenomena 25 BCE To 32 CE.” Astronomical Applications Department of the U.S. Naval Observatory. 13 December 2011. <http://web.archive.org/web/20180126214204/http://aa.usno.navy.mil/faq/docs/SpringPhenom.php> “The Scientific Method by Science Made Simple.” ScienceMadeSimple.com. 2014. <http://web.archive.org/web/20211228113808/https://www.sciencemadesimple.com/scientific_method.html> Calendars for 28-33 AD. TimeandDate. 2022. <https://www.timeanddate.com/calendar/custom.html?year=27&country=1&hol=0&cdt=31&holm=1&df=1>

[11] Matthew 27:45; Mark 15:33; Luke 23:44.

[12] “Phases of the Moon: 0001 to 0100 Universal Time (UT).” Astropixels.com.

[13] Espenak, Fred. National aeronautics and Space Administration. “Solar Eclipses of Historical Interest.” Java script. 2009. <https://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/SEhistory/SEhistory.html> Espenak, Fred. National aeronautics and Space .Administration. “Total Solar Eclipse of 0033 March 19.” Chart. 2009. <https://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/SEhistory/SEplot/SE0033Mar19T.pdf> “Phases of the Moon: 0001 to 0100 Universal Time (UT).” Astropixels.com.

[14] Espenak, Fred. NASA Eclipse Website. “Lunar Eclipses from -0099 to 0000 Jerusalem, Israel.” n.d <https://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/JLEX/JLEX-AS.html>

[15] Peck, Harry Thurston. Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities. “Iudaei.” 1898. <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0062:entry=iudaei-harpers&highlight=antipas> CR Josephus, Flavius. Antiquities of the Jews. Trans. and commentary. William Whitson. The Complete Works of Josephus. Book XVII, Chapter XI.4; Book XVIII, Chapter II.1. <http://books.google.com/books?id=e0dAAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=fal > Josephus, Flavius. Wars of the Jews. Trans. and commentary. William Whitson. The Complete Works of Josephus. Book II, Chapter IX.1. <http://books.google.com/books?id=e0dAAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false>

[16] Josephus. Antiquities. Book XVIII, Chapter IV.6; Chapter V.1. Josephus. Wars. Book II, Chapter IX.1. Strabo. Geography. Hamilton, H.C., Ed. Book 16, Chapter 2, footnotes 125, 128. <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0239:book=16:chapter=2&highlight=antipas>

[17] Josephus. Antiquities. Book XVIII, Chapter II. 2, Chapter VI. 10. Josephus. Wars of the Jews. Book II, Chapter IX.6. Grant, Michael. Encyclopædia Britannica. “Augustus.” 2022. <https://www.britannica.com/biography/Augustus-Roman-emperor> Pohl, Frederik. Encyclopædia Britannica. “Tiberius.” 2022. <https://www.britannica.com/biography/Tiberius> “Tiberius.” Wasson, Donald L. World History Encyclopedia. 19 July 2012 <https://www.worldhistory.org/Tiberius>

[18] Josephus. Antiquities. Book XVII, Chapter XIII. 2, 5; Book XVIII, Chapters II.2; VI.1-2, 5-7, 10. Josephus. Wars. Book II, Chapter 9.5. Tacitus. Annals. Books II, XV. Suetonius (C. Suetonius Tranquillus or C. Tranquillus Suetonius). Suetonius (C. Suetonius Tranquillus or C. Tranquillus Suetonius). The Lives of the Twelve Caesars. Tiberius, #50, 51, 52. <http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Suetonius/12Caesars/home.html> “Valerius Gratus.” Encyclopedia.com. 2019. <https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/valerius-gratusdeg>

[19] Josephus. Antiquities. Book XVIII, Chapter IV.1-2.

[20] “High Priest.” Jewish Encyclopedia. 2007. < https://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/7689-high-priest>

[21] Josephus. Antiquities. Book XVIII, Chapters I1.2; IV.3; V.3; Book XIX, Chapter VI.2. “High Priest.” Jewish Encyclopedia. “Jewish Palestine at the time of Jesus.” Britannica Encyclopedia. 2022. <https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jesus/Jewish-Palestine-at-the-time-of-Jesus#ref748553> “Pontius Pilate.” Biography. 2021. <https://www.biography.com/religious-figure/pontius-pilate> Pilate, Pontius.” Encyclopedia.com. 2022. <https://www.encyclopedia.com/people/philosophy-and-religion/biblical-proper-names-biographies/pontius-pilate> “Tiberius.” World History Encyclopedia. <https://www.worldhistory.org/Tiberius> <https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jesus/Jewish-Palestine-at-the-time-of-Jesus#ref748553> Smith, Mark. History News Network. “The Real Story of Pontius Pilate? It’s Complicated.” 2022. <https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/168311> Larson, Rick. The Star of Bethlehem. 2022. <https://bethlehemstar.com/the-day-of-the-cross/pilate-and-sejanus>

[22] Josephus. Antiquities. Book XVIII, Chapter IV.1-2.

[23] Peck, Harry Thurston. Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities. 1898. #3. <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0062:entry=herodes-harpers&highlight=antipas> CR Josephus. Antiquities. Book XVIII, Chapter V.1.

[24] Quran 3:19:2-7, 6:85; 19:7. <https://bible-history.com/links/aretas-1067> Josephus. Antiquities. Book XVIII, Chapter V.2, Chapter II.3, V; Chapter V.4. A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Ed. William Smith. “Salo’me.” 1848. <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0104:entry=salome-bio-4&highlight=tetrarch> A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. “Hero’des I. or Hero’d the Great or Hero’des Magnus.” <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0104:entry=herodes-i-bio-1&highlight=tetrarch> CR Matthew 14:5; Mark 6:19-20; Luke 3:19-20. CR Josephus. Antiquities. Book XVIII, Chapter V.4..

[25] Josephus. Antiquities. Book XVIII, Chapter V.2.

[27] Josephus. Antiquities. Book XVIII, Chapter V.1. “Herod Antipas.” Britannica Encyclopedia. 2022. <https://www.britannica.com/biography/Herod-Antipas> “Aretas.” Bible History. 2022. <https://bible-history.com/links/aretas-1067> Gertoux, Gerard. “Dating the death of Herod.” Academia.edu. p 123. 2015. <http://www.academia.edu/2518046/Dating_the_death_of_Herod> Last accessed 28 Mar. 2023. “Herod Antipas.” Livius.org. n.d.<https://www.livius.org/articles/person/herod-antipas/> “Aretas ( in Aramaic ) IV.:” Jewish Encyclopedia. n.d. <https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/1752-aretas>

[28] Josephus. Antiquities. Book XVIII, Chapter V.1.

[29] Josephus. Antiquities. Book XVIII, Chapter V.1-3.

[30] Josephus. Antiquities. Book XVIII, Chapter VI. 10.Strabo. Geography. Chapter V. n.d. <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0239:book=12:chapter=5&highlight=tetrarch> “Tetrarcha.” A Dictionary of Green and Roman Antiquities. 1890. <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0063:entry=tetrarcha-cn&highlight=tetrarch>

[31] CR Matthew 14:1, 3-4, 5, 6; Mark 6:14-20, 21; Luke 3:19; 4:16-30; 7:24-30; 8:3; 9:7, 9, 13.31; 23:7, 9, 11, 12, 15; John 1:28-34. CR Acts 4:27; 12:4, 6, 11, 19, 21, 23; 13;1; 23:8, 35. Josephus. Antiquities. Book XVII, Chapter John 1:28-34. XI.4; Book XVIII, Chapter V.1 Josephus. Wars of the Jews. Book II, Chapter IX.1; Book III, Chapter X.7.

[32] John 1:35-47; 2:1-13. CR Matthew 4:13; 13:53-58. Mark 6:1-4.

[33] John 5:35. CR Matthew 4:12; 11:2-7; John 5:32-33, 7:18-25.

[34] Matthew 14:5; Mark 6:19-20; Luke 3:19-20. CR Josephus. Antiquities. Book XVIII, Chapter V.4. “Hero’des I. or Hero’d the Great or Hero’des Magnus.”

[35] John 10:40-41; 11:54-12:18.

[36] A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. “Salo’me.”

[37] Matthew 14:3-10; Mark 6:17-27; Luke 3:19