Psalms – Any Messiah Prophecies?

Psalms verses are quoted in the New Testament more than any other. The book includes praises, songs, travails, and salvation; and characteristics of God including some that pertain to the Messiah.[1]

Raising the bar to the highest level, some Psalms are identified by Jesus of Nazareth as prophecies to be fulfilled by himself – they must be fulfilled if his claim to be the Messiah is credible.[2]

MT: 5:17-18 “Do not think that I have come to abolish the law or the prophets; I have come not to abolish but to fulfill. For truly I tell you, until heaven and earth pass away, not one letter, not one stroke of a letter, will pass from the law until all is accomplished.”(NRSV)* [3]

Judaism regards Psalms 118 as the concept of salvation pointing to the arrival of the Messiah recited in the Hallel during Festival holidays. In it’s article entitled “Hosanna,” Jewish Encyclopedia says Psalms 118 refers to “…the advent of the Messiah (see Midr. Teh. to Ps. cxviii. 17, 21, 22; comp. Matt. xxi. 42).” [4]

PS 118:22-23 The stone which the builders rejected Has become the chief cornerstone. This was the LORD’S doing; It is marvelous in our eyes. (NKJV)

MT 21:42 Jesus said to them, “Have you never read in the Scriptures: ‘The stone which the builders rejected Has become the chief cornerstone. This was the LORD’S doing, And it is marvelous in our eyes’?”(NKJV)

Jewish sage Rabbi Rashi viewed Micah 5:1(2) as a prophecy predicting the Messiah would be born in Bethlehem. In his phrase-by-phrase commentary of the Bethlehem prophecy, the Rabbi quoted from Psalms 118.22:

“from you shall emerge for Me the Messiah, [Rabbi Rashi:) son of David, and so Scripture says (Ps. 118:22): ‘The stone the builders had rejected became a cornerstone.”

Visiting Bethany just days before entering Jerusalem for the last time, oddly some Pharisees warned Jesus to watch out for Tetrarch Herod Antipas who wanted to kill him. Ignoring the warning, Jesus said he was busy casting out demons and performing cures, then finished by quoting from Psalms 118:

PS .118:26 “Blessed is he who comes in the name of the LORD! We have blessed you from the house of the LORD.”(NKJV)

LK 13:35 “I say to you, you shall not see Me until the time comes when you say, ‘Blessed is He who comes in the name of the LORD!’”(NKJV)

Days later, Jesus rode into Jerusalem seated on the unbroken colt of a donkey while a crowd of people placed palm branches in his path chanting from Psalms 118:26.[6] All four Gospel authors write about that triumphal day:[7]

JN 12:12-13 “… a great multitude that had come to the feast, when they heard that Jesus was coming to Jerusalem, took branches of palm trees and went out to meet Him, and cried out: “Hosanna! ‘Blessed is He who comes in the name of the LORD!’ The King of Israel!””[8]

Teaching in the Temple just 3 days before he would be crucified, the Pharisees again questioned Jesus by what authority he was teaching. His answer included one of the few parables common to Matthew, Mark and Luke.[9]

Winery tenants, in the parable, refused to pay rent and beat-up those sent to collect it, then even stoned to death the owner’s only son when he personally attempted to collect the rent. Reaction by the Pharisee’s: “Bring those wretches to a wretched end!”[10]

Psalms 118:22-23 was cited by Jesus when he responded to them. Pharisees became angry when they realized the parable was about themselves.[11]

Passover meal became “The Last Supper” for Jesus and as they were eating, Jesus identified dark words from Psalms 41:9 soon to be fulfilled.[12] Jesus said it was a prophecy imminently to be fulfilled to show who he is:[13]

PS 41:9 Even my close friend, whom I trusted, he who shared my bread, has lifted up his heel against me. (NIV)

JN 13:18-19 “I am not referring to all of you; I know those I have chosen. But this is to fulfil the scripture: ‘He who shares my bread has lifted up his heel against me.’ “I am telling you now before it happens, so that when it does happen you will believe that I am He. (NIV)[14]

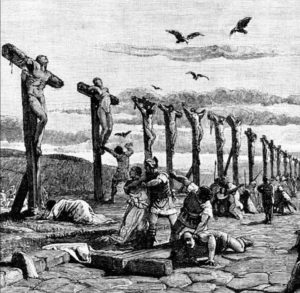

Psalms 22 is generally recognized by Christianity as either a foreshadowing or prophecy about the crucifixion of Jesus. Written about 1000 years earlier, it describes agonizing physical and mental effects remarkably matching an execution by Roman crucifixion and foretold what other people would say and do.

Prophecies are challenging due to many factors and, in some cases, it may be clarified by other prophecies. A prophecy is often not fully or clearly understood until a full realization that the foretold event did, in fact, occur.[15]

If specific Psalms about the Messiah came true during the appearance of Jesus of Nazareth, does it make them Messiah prophecies?

* Greek word nomos translated as “law” means “anything established, anything received by usage, a custom, a law, a command” i.e. the word includes the Law of Moses as well as other established customs or traditions.

Updated June 20, 2025.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

REFERENCES:

[1] “44 Prophecies Jesus Christ Fulfilled.” Roman Catholic Church of St Thomas More, Swiss Cottage. n.d. <https://parish.rcdow.org.uk/swisscottage/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2014/11/44-Prophecies-Jesus-Christ-Fulfilled.pdf> Kranz, Jeffrey. “Which Old Testament Book Did Jesus Quote Most?” 2014. <http://blog.biblia.com/2014/04/which-old-testament-book-did-jesus-quote-most> Morales. L. Michael “Jesus and the Psalms.” TheGospelCoalition.org. 2011. <https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/jesus-and-the-psalms> Wilson, Ralph F. “10. Psalms: Looking Forward to the Messiah.” (Psalms 2, 110, and 22).” JesusWalk.com. 2020. <http://www.jesuswalk.com/psalms/psalms-10-messianic.htm> Rochford, James M. Evidence Unseen. The Psalms. image. n.d. <https://www.evidenceunseen.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/psalminternet-1024×538.jpg> “Hallel.” MyJewishLearning.com. 2020. <https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/hallel>

[2] Luke 24:44.

[3] “nomos <3551>.” Greek text. Net.Bible.org. 2020. <http://classic.net.bible.org/strong.php?id=3551> “G3551” LexiconConcordance.com. n.d. <http://lexiconcordance.com/greek/3551.html>

[4] “Psalms 118.” JewwishAwareness.org. 2011. <http://www.jewishawareness.org/psalm-118> McKelvey, Michael G. “The Messianic Nature of Psalm 118.” Reformed Faith & Practice. 2017. <https://journal.rts.edu/article/messianic-nature-psalm-118> “Hallel” EncyclopædiaBritannica. 2020. <https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hallel

[5] “Hosanna.” Jewish Encyclopedia. <http://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/7893-hosanna> CR Mark 12:11; Luke 20:17.

[6] “Hosanna.” Jewish Encyclopedia. 2011. <http://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/7893-hosanna>

[7] CR Matthew 21:2-11; Mark 11:1-11; Luke 19:28-40; John 12:12-16.

[8] NKJV.

[9] Matthew 21:33-41; Mark 12:1-12; Luke 20:9-19.

[10] Matthew 21:42. NIV, NASB.

[11] Matthew 21:46.

[12] Matthew 26:17-19; Mark 14:12-16; Luke 22:7-20; John 13:1-3.

[13] CR Matthew 26:21-25; Mark 14:17-21; Luke 22:21-23.

[14] CR Matthew 26:46-56; Mark 14:42-52; Luke 22:47-53; John 18:1-11a.

[15] Bugg, Michael. “Types of Prophecy and Prophetic Types.” Hebrew Root. n.d. <http://www.hebrewroot.com/Articles/prophetic_types.htm> Brooks, Carol. “Prophecy.” InPlainSite.org. <http://www.inplainsite.org/html/old_testament_prophecy.html> “Plaster Miodu. Psalm 22: Na krańce ciemności.” (translated: “Honeycomb. Psalm 22: To the ends of darkness.”) YouTube. image. 2015. <https://i.ytimg.com/vi/rUjYzzjEHfw/maxresdefault.jpg>

Jewish historian

Jewish historian