The Great Isaiah Scroll – Science Revelations

Isaiah is considered to be the greatest of all the prophets by Judaism and Christianity making the Book of Isaiah the greatest of all the prophetic books in the Bible.[1] Many references and interpretations of Isaiah’s prophecies are found in the Talmud with Sanhedrin tractate 98 alone making ten references.[2]

Paramount to the prophecies of Isaiah is having confidence that his prophecies are reflected accurately in today’s Bibles.[3] Sciences of archeology and textual criticism enhanced by technology play a major role in confirming that determination.

Produced from 285-247 BC, the Septuagint LXX translation is the primary foundation for Christian Bibles. “Septuagint” in Latin means 70 and the Roman Numeral “LXX,” thus the name representing those who worked together on the translation.[4]

Josephus, a Jewish Pharisee, described the origin of the Septuagint translation. Egypt ruler Ptolemy Philadelphius wrote to Priest Eleazar in Jerusalem requesting six of the best elders from each of the 12 tribes of Israel to make a Greek translation from the official Hebrew text.[5]

Elders including priests traveled to Egypt with scrolls from the Temple for the translation project.[6] King Ptolemy was most impressed with the condition of the scrolls “admiring the thinness of those membranes, and the exactness of the junctures; which could not be perceived, (so exact were they connected one with another;)…”[7]

Upon completion, the Greek translation was reviewed again by “both the priests and the ancientest of the elders, and the principal men…” The Septuagint was finalized by Ptolemy with a promise that it would never be changed.[8]

Hebrew Bible translations are based on two surviving Hebrew Masoretic Texts (MT), the Aleppo Codex dated to 925 AD and the Leningrad Codex circa 1008-10 AD.[9] About a third of the Aleppo text was destroyed in a synagogue fire resulting in a dependency on the Leningrad manuscript to fill in the missing text.

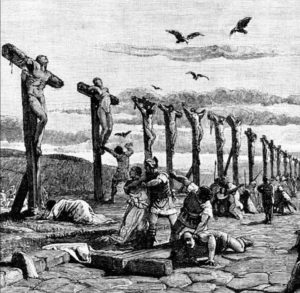

Spanning the timeline between the Septuagint and the MT is at least 1150 years when many events transpired in Judea– the Greek Empire with its language and Hellenism influences; the rule of King Herod; and domination by the Roman Empire which destroyed Jerusalem with the Temple in 70 AD.[10] These seismic events affected the purity of the MT translations.

Addressing these impacts opened the door to the Miqraot Gedolot HaKeter Project to produce a “precise letter-text” translation of the Masoretic text. Director Menachem Cohen, Professor of Bible at Bar-Ilan University of Israel, said the project was intended to address the “thousands of flaws of the previous and current editions.”[11]

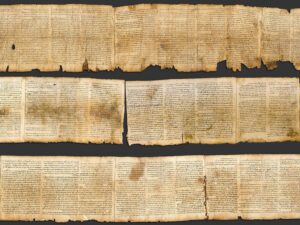

Dead Sea Scroll discoveries at Qumran, beginning in 1947 continuing over the next decade until 1956, revealed a treasure trove of ancient scrolls determined to be about 2000 years old.[12] Two scrolls of Isaiah were among the discoveries, one virtually complete scroll known as “Qa” and the second scroll known as “Qb,” about 75% complete.[13]

For good reason, the Qa scroll has been dubbed “The Great Isaiah Scroll” and is on display in Jerusalem at the Shrine of the Book.[14] The Scroll can be viewed in its entirety on the Internet.[15]

Dated to c. 125 BC, The Scroll is compromised of 17 pieces of leather sewn together, each strip containing from 2 to 4 pages of text.[16] It serves as a side-by-side, older Hebrew text comparison and precludes the claim of any Christian influences because it predates the arrival of Jesus of Nazareth.

A precept of the science of textual criticism is the shorter the time interval between the original and the existing text, the greater the level of textual purity. Shorter time frame assumes fewer handwritten copies were produced where variations are inevitably introduced.[17]

Translation nuances are to be expected in the Greek translation because some ancient Hebrew characters do not have a direct Greek equivalent.[18] As with any translation, some words or phrases must be deciphered by the translators with a heavy dependence on the context.[19]

Josephus’ account that translation of the Greek Septuagint is based solely on side-by-side Hebrew text from the Temple suggests textual purity of the highest degree.[20] Inevitably, the lack of not having a side-by-side Hebrew text significantly impacted the MT purity.

Text variations posed a huge challenge to the Miqraot Gedolot HaKeter Project team. Even the spelling of “Israel” appeared differently.[21]

“…the aggregate of known differences in the Greek translations is enough to rule out the possibility that we have before us today’s Masoretic Text. The same can be said of the various Aramaic translations; the differences they reflect are too numerous for us to class their vorlage as our Masoretic Text.” – Menachem Cohen[22]

Focus is placed only on the two major controversial prophecies of 7:14 and the chapters 52-53 parashah. Differences are found in the very small vowel punctuations seen more easily with technology enhancements.[23]

“The major difference between the Aleppo Codex and the Dead Sea Scrolls is the addition of the vowel pointings (called nikkudot in Hebrew) in the Aleppo Codex to the Hebrew words.” – Jeff A Benner[24]

Several potentially meaningful differences between the MT and Septuagint are reflected by The Scroll.[25] Written entirely in the future tense, 7:14 is an undisputed prophecy.

Variations include the translation of the two controversial Hebrew words ha-alamah, a text pronoun difference and two name differences.[26] Most significantly, the MT translates ha-almah as “a young woman” while The Scroll translates the words as “a young maiden.”

According to Rabbi Maimonides, a “virgin maiden” is a female who has not reached the age of maturity (between 12 1/2 and 13 years of age); a “woman” implies she is not a minor.[27] “Woman” does not imply virginity.

Hebrew ha exclusively means “the” – specific to the noun that follows.[28] Septuagint translates the Hebrew words ha-almah into Greek as “ha Parthenos” precisely meaning “the virgin.”[29]

YHWH (Yehweh), the name of God, is used in the The Scroll equivalent to verse 7:14. MT translations use the more generic word Adonai for “Lord.”[30]

Pronoun differences in 7:14 could be impactful. The Scroll implies Yahwah (God) will call his name Immanuel, written as the single word indicating a name and the MT says “she” will call his name Immanu-el suggesting the mother.[31]

Other differences found in The Scroll are mostly grammatical and do not change the general text.[33] Interestingly, in Column XLIV of The Scroll begins the Isaiah 52-53 parashah with the reference to “my servant.”[32]

Written in the margin of The Scroll, equivalent to verse 53:2, is a note that reads “before us” or “him.” Typically, the verse uses a male pronoun in both Jewish and Christian Bibles; however, The Complete Jewish Bible uses “it” referring to the nation of Israel, according to Rabbi Rashi.[34]

A significant issue between the Septuagint and the MT in verse 53:4 remains unresolved by The Scroll using the Hebrew word חֹ֑לִי (choliy). Bible translators have used a myriad of words: “pain,” “weakness,” “sorrows,” “grief,” “suffering” “sickness,” “evil,” “illness,” “infirmities,” or “disease.”[35]

One possibly noteworthy difference, equivalent to verse 53:11, is the word nephesh/nap̄·šōw translated most commonly as “life” while other translations sometimes use the word “soul” or “light.” Other Christian and Jewish Bibles including the MT translate the word as “it.”[36]

How likely is it that The Great Isaiah Scroll accurately reflects the original Hebrew text written by the prophet Isaiah?

Updated February 2, 2025.

This work is licensed under aCreative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

BSB = Berean Study Bible

CSB = Christian Standard Bible

ISV = International Standard Version

NAB = New American Bible

NHEB = New Heart English Bible

NIV = New International Version

NRSV = New Revised Standard Verson

WEB = World English Bible

REFERENCES:

[1] “Isaiah.” Jewish Encyclopedia. 2011. <http://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/8235-isaiah> “Isaiah.” Biblica | The International Bible Society. 2019. <https://www.biblica.com/resources/scholar-notes/niv-study-bible/intro-to-isaiah>

[2] Soncino Babylonian Talmud. Sanhedrin 98a, footnote #1. Isaiah XLIX:7, XVIII:5, I:25, LIX:19, LIX:20, LX:21, LIX:16, XLVIII:11, LX:22, LIII.4. <https://israelect.com/Come-and-Hear/sanhedrin/sanhedrin_98.html#98b_31> CR The Babylonian Talmud. Trans. Michael L. Rodkinson. 1918. Sanhedrin, Chapter XI, p 310. <http://www.sacred-texts.com/jud/t08/t0814.htm>

[3] Cohen, Menachem. “The Idea of the Sanctity of the Biblical Text and the Science of Textual Criticism.” Bar-Ilan University. 1979. <http://cs.anu.edu.au/%7Ebdm/dilugim/CohenArt> Benner, Jeff A. “The Great Isaiah Scroll and the Masoretic Text.” Ancient Hebrew Research Center. 2017. <http://www.ancient-hebrew.org/bible_isaiahscroll.html> Zeolla, Gary F. Universitat De Valencia. “Textual Criticism.” 2000. <http://www.uv.es/~fores/programa/introtextualcritici.html> “Isaiah.” Biblica | The International Bible Society. 2019. <https://www.biblica.com/resources/scholar-notes/niv-study-bible/intro-to-isaiah>

[4] “Septuagint.” Definitions.net. n.d. <https://www.definitions.net/definition/septuagint> “Septuagint.” Merriam-Webster. 2020. <https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Septuagint> Josephus. Antiquities. Book XII, Chapter II.7, 11. Whitson. The Complete Works of Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews. Book XII, Chapter.II.12, footnote *.

[5] Josephus, Flavius. Antiquities of the Jews. Trans. and commentary. William Whitson. The Complete Works of Josephus. 1850. Book XII, Chapter II. <http://books.google.com/books?id=e0dAAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false> “Septuagint.” Septuagint.Net. 2014. <http://septuagint.net> Benner. “The Great Isaiah Scroll.” Lundberg, Marilyn J. “The Leningrad Codex.” USC West Semitic Research Project. 2012. <https://web.archive.org/web/20140826133533/https://www.usc.edu/dept/LAS/wsrp/educational_site/biblical_manuscripts/LeningradCodex.shtml> “Septuagint.” Encyclopædia Britannica. 2019. <https://www.britannica.com/topic/Septuagint> Cohen. “The Idea of the Sanctity of the Biblical Text and the Science of Textual Criticism.”

[6] Josephus. Antiquities. Book XII, Chapter II. 5-6, 11-13. Whitson, William. The Complete Works of Josephus. 1850. Antiquities of the Jews. Book XII, Chapter.II.12, footnote *.

[7] Josephus. Antiquities. Book XII, Chapter II.11.

[8] Josephus. Antiquities. Book XII, Chapter II.13.

[9] Abegg,, et al. The Dead Sea Scrolls. “Introduction”, page x. Aronson, Ya’akov. “Mikraot Gedolot haKeter–Biblia Rabbinica: Behind the scenes with the project team.” Association Jewish Libraries. Bar Ilan University. Ramat Gan, Israel. n.d. <http://www.jewishlibraries.org/main/Portals/0/AJL_Assets/documents/Publications/proceedings/proceedings2004/aronson.pdf> Miller, Laura. “The Aleppo Codex: The bizarre history of a precious book.” 2012. Salon. <http://www.salon.com/2012/05/13/the_aleppo_codex_the_bizarre_history_of_a_precious_book>

[10] “Scrolls from the Dead Sea.” Library of Congress. n.d. <https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/scrolls/late.html> Greenberg, Irving. “The Temple and its Destruction.” MyJewishLearning.com. 2020. <https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/the-temple-its-destruction> “Destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE.” Harvard Divinity School. 2020. <https://rlp.hds.harvard.edu/faq/destruction-second-temple-70-ce>

[11] Cohen, Menachem. “Mikra’ot Gedolot – ‘Haketer’ – Isaiah.” 2009. <http://www.biupress.co.il/website_en/index.asp?id=447>

[12] “Dead Sea Scrolls.” Archaeology. 2018. <http://www.allaboutarchaeology.org/dead-sea-scrolls.htm> “Scrolls from the Dead Sea.” Library of Congress. Roach, John. “8 Jewish archaeological discoveries – From Dead Sea Scroll to a ‘miracle pool.’” Science on NBCNEWS.com. <http://www.nbcnews.com/id/28162671/ns/technology_and_science-science/t/jewish-archaeological-discoveries/#.VLU34XtFYuI> “The Great Isaiah Scroll.” The Digital Dead Sea Scrolls. 2020. <http://dss.collections.imj.org.il/isaiah> Benner. “The Great Isaiah Scroll.” “Isaiah.” Biblica.

[13] Miller. Fred P. “The Great Isaiah Scroll.” Moellerhaus Publisher. Directory. 1998. <http://www.moellerhaus.com/qumdir.htm> Cohen. “The Idea of the Sanctity of the Biblical Text.” Footnote #4. Abegg, Jr., Martin G., Flint, Peter W. and Ulrich Eugene Charles. The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible: the oldest known Bible translated for the first time into English. 2002. <https://books.google.com/books?id=c4R9c7wAurQC&lpg=PP1&ots=fQpCpzCdb5&dq=Abegg%2C%20Flint%20and%20Ulrich%2C%20The%20Dead%20Dead%20Sea%20Scrolls%20Bible%2C&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q=Isaiah&f=false>

[14] Benner. “The Great Isaiah Scroll.” Abegg,, et al. “The Dead Sea Scrolls.” “The Great Isaiah Scroll.” AllAboutArchaeology. photo. 2021. <https://www.allaboutarchaeology.org/great-isaiah-scroll-faq.htm>

[15] “The Great Isaiah Scroll.” The Digital Dead Sea Scrolls.

[16] Miller. Fred P. “Q” = The Great Isaiah Scroll Introductory Page” Chapter I, IV. Moellerhaus Publisher. 2016. <http://www.moellerhaus.com/Controversy/Controversy.htm> Benner, Jeff A. “The Great Isaiah Scroll and the Masoretic Text.” “textus receptus.” The Free Dictionary. 2020. <https://www.thefreedictionary.com/Received+Text#:~:text=The%20text%20of%20a%20written,of%20recipere%2C%20to%20receive.%5D> “The Great Isaiah Scroll.” The Digital Dead Sea Scrolls. “Exploring Qumran: The Dead Sea Scrolls Community.” MSN.com. video. 2025. <https://www.msn.com/en-us/video/peopleandplaces/exploring-qumran-the-dead-sea-scrolls-community/vi-AA1xfbCq?ocid=msedgntp&pc=HCTS&cvid=4e309000c75e45b69d296288be2ab1f9&ei=287#details>

[17] Westcott, Brooke F. & Hort, John A. The New Testament in the Original Greek – Introduction|Appendix. pp 31, 58-59, 223-224, 310-311. 1907. <https://books.google.com/books?id=gZ4HAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=The+New+Testament+in+the+Original+Greek&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiOjMvk3fjXAhUE5yYKHSTHC5wQ6wEIOjAD#v=onepage&q=The%20New%20Testament%20in%20the%20Original%20Greek&f=false> Miller. Fred P. The Great Isaiah Scroll. 1998. “Qumran Great Isaiah Scroll.” Benner. “The Great Isaiah Scroll.” Cohen, Menachem. “The Idea of the Sanctity of the Biblical Text and the Science of Textual Criticism.”

[18] Welch, Adam Cleghorn. “Since Wellhausen.” p 175. <https://biblicalstudies.org.uk/pdf/expositor/series9/1925-09_164.pdf> Benner, Jeff A. “Introduction to Ancient Hebrew.” <https://www.ancient-hebrew.org/introduction.htm>

[19] Benner. “Introduction to the Hebrew Bible.”

[20] Schodde, George H. Old Testament Textual Criticism. pp 45-46. 1887. <https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdfplus/10.1086/469936> Gentry, Peter J. “The Text of the Old Testament.” p 24. 2009 <https://www.etsjets.org/files/JETS-PDFs/52/52-1/JETS%2052-1%2019-45%20Gentry.pdf>

[21] Cohen. “The Idea of the Sanctity of the Biblical Text.” CR Miller. Fred P. “The Translation of the Great Isaiah Scroll.” Book of Isaiah. Trans. Fred P. Miller. Moellerhaus Publisher. 2001. <http://www.moellerhaus.com/qa-tran.htm> Benner, Jeff A. “The Great Isaiah Scroll and the Masoretic Text.” Mikra’ot Gedolot. Bar-Ilan University. n.d. <https://www.biu.ac.il/en/about-bar-ilan/jewish-heritage/mikraot-gdolot>

[22] Cohen. “The Idea of the Sanctity of the Biblical Text.”

[23] Cohen. “The Idea of the Sanctity of the Biblical Text.” Footnotes #6-7.

[24] Benner, Jeff A. “The Great Isaiah Scroll and the Masoretic Text.”

[25] Miller. Fred P. “The Translation of the Great Isaiah Scroll.” “The Translation of the Great Isaiah Scroll “Dead Sea Scrolls Bible Translations.” 2016. <http://dssenglishbible.com/scroll1QIsaa.htm>

[26] Miller, Fred P. “Column VI – The Great Isaiah Scroll 6:7 to 7:15.” Ancient Hebrew Research Center. n.d. <http://www.moellerhaus.com/qum-6.htm>

[27] Miller. “Column VI – The Great Isaiah Scroll 6:7 to 7:15.” Miller. Fred P. “Assyrian Destruction of Israel is Not the End God Will Bring the Messiah to the Same Territory and the Same Restored People.” Chapters 7-8. Ancient Hebrew Research Center. n.d. <http://www.moellerhaus.com/7-8.htm#alma> Benner, Jeff A. “Textual Criticisim of Isaiah 7:14 (Video).” 2020. <https://www.ancient-hebrew.org/textual-criticism/textual-criticism-of-isaiah-7-14.htm> “Dead Sea Scrolls Bible Translations.” Mishneh Torah, Forbidden Intercourse 17.” Sefaria.org. Footnotes #48 & 49. n.d. <https://www.sefaria.org/Mishneh_Torah%2C_Forbidden_Intercourse.17.13?lang=bi&with=Navigation&lang2=en>

[28] Benner. “Introduction to the Ancient Hebrew Alphabet.”

[29] Miller. “Column VI – The Great Isaiah Scroll 6:7 to 7:15.”

[30] Benner, Jeff A. “What isthe difference between lord, Lord and LORD?” Ancient Hebrew Research Center. 2020. https://www.ancient-hebrew.org/god-yhwh/difference-between-lord-Lord-and-LORD.htm

[31] Benner, Jeff A. “Column VI – The Great Isaiah Scroll 6:7 to 7:15.” Miller. Fred P. “The Translation of the Great Isaiah Scroll.” Lines #28-29. Isaiah 7:14. NetBible.org. LXXM. <https://classic.net.bible.org/verse.php?book=Isa&chapter=7&verse=14>

[32] Miller. Fred P. “The Translation of the Great Isaiah Scroll.”

[33 Cohen. “The Idea of the Sanctity of the Biblical Text.” Footnote #4. Benner, Jeff A. “The Great Isaiah Scroll and the Masoretic Text.”

[34] Miller. “The Translation of the Great Isaiah Scroll.” Miller, Fred P. Moellerhaus Publishers. “Column XLIV – The Great Isaiah Scroll 52:13 to 54:4.” n.d. <http://www.moellerhaus.com/qum44.htm> “Dead Sea Scrolls Bible Translations.” 1Q Isaiaha, <http://dssenglishbible.com/scroll1QIsaa.htm> “Isaiah 53 at umran,” Hebrew Streams. <http://www.hebrew-streams.org/works/qumran/isaiah-53-qumran.pdf> Isaiah 53:2. Biblehub.com. <https://biblehub.com/isaiah/53-2.htm> Isaiah 53:2. NetBible.org. <http://classic.net.bible.org/verse.php?book=Isa&chapter=53&verse=2> Yisheyah (Book of Isaiah) JPS translation. Breslov.com. 1998. <http://www.breslov.com/bible/Isaiah53.htm#2> Yeshayahu – Isaiah – Chapter 53. Chabad.org. Complete Jewish Bible translation. 2020. <https://www.chabad.org/library/bible_cdo/aid/15984> Sefari. Sefaria.org. William Davidson translation. 2024. <https://www.sefaria.org/texts>

[35] Miller. “The Translation of the Great Isaiah Scroll.” Benner, Fred P. “The Great Isaiah Scroll and the Masoretic Text.” 2020. <https://www.ancient-hebrew.org/dss/great-isaiah-scroll-and-the-masoretic-text.htm#2> “Dead Sea Scrolls Bible Translations.” 2016. <http://dssenglishbible.com/scroll1QIsaa.htm> “Isaiah 53 at Qumran.” NetBible.org. n.d. <https://classic.net.bible.org/verse.php?book=Isa&chapter=53&verse=4> H2483. LexiConcordance.com. n.d. <http://lexiconcordance.com/hebrew/2483.html>

[36] “Isaiah 53:11.” BibleHub.com. Lexicon & Interlinear. 2020. <https://biblehub.com/isaiah/53-11.htm> “Isaiah 53:11.” NetBible.org. Hebrew text. 2020. <http://classic.net.bible.org/verse.php?book=Isa&chapter=53&verse=11> “H5315.” Lexicon-Concordance. n.d. <http://lexiconcordance.com/hebrew/5315.html> Isaiah 53:11. JPS translation. Isaiah 53:11. Complete Jewish Bible. Isaiah 53 :11. “Isaiah 53 at Qumran,” Benner, Jeff A. “The Great Isaiah Scroll and the Masoretic Text.” Miller. “Column XLIV – The Great Isaiah Scroll 52:13 to 54:4.” n.d. <http://www.moellerhaus.com/qum-44.htm> Miller. “The Translation of the Great Isaiah Scroll.” “Dead Sea Scrolls Bible Translations.” 1Q Isaiahb. Footnote (2). 2016. <http://dssenglishbible.com/scroll1QIsab.htm>

Jewish historian

Jewish historian