Jordan River – Its Significance

Mentioned almost 200 times from Genesis to the Gospels, the Jordan River plays an important role throughout. The River has served as a boundary, a landmark, the place of several miracles, John the Baptist’s ministry and in it Jesus of Nazareth was baptized.

First reference in the Bible to the Jordan River is implied in Genesis 13 when Abram gave his nephew, Lot, a choice where to live with his family and livestock. Seeing the fertile “plain of the Jordan,” Lot made his decision and, by default, Abram took the land west of the Jordan – Canaan.[1]

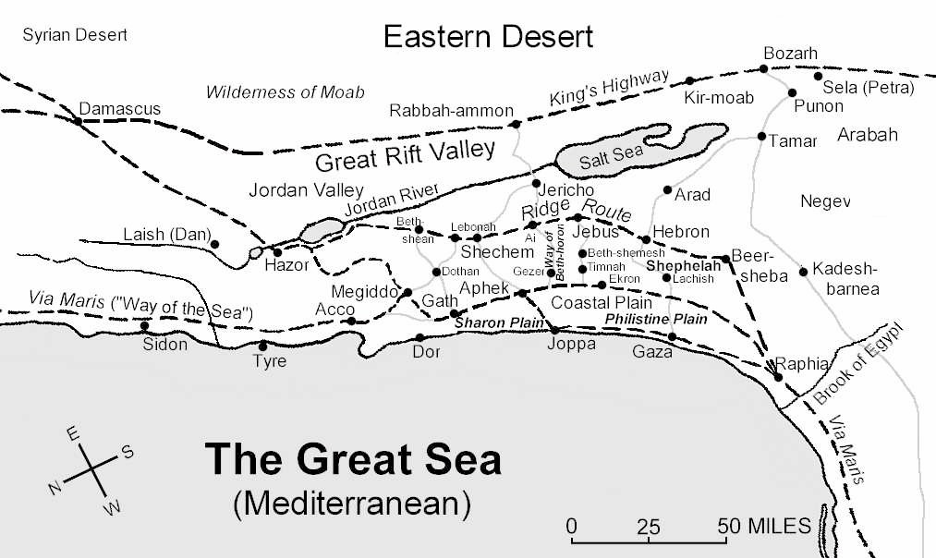

God promised Abram the land he could see in all four directions would belong to him and his descendants forever. The Jordan River marked the boundary between the two lands of Canaan and the Arabah.[2]

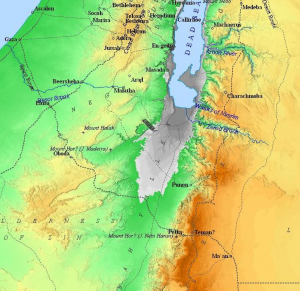

Lowest elevation of all the rivers of the world, the head waters of the Jordan feed into the Sea of Galilee (aka Chinnereth, Lake Tiberius, Lake Kinneret) on the north end, exiting on the south end of the Sea. From there, the River covers a mere 65 land miles to the Dead Sea where it ends. Normal width of the Jordan River ranges between 30 to 100 feet and its depth of only 10 to 17 feet.

Either side of the River forms the Jordan River Valley expanding up to 15 miles wide. The northern valley contains fertile land, but by the time it reaches the southern end at the Dead Sea near Jericho, the terrain is hot and arid.[3]

Not exactly a big river, it is the rapid current that makes it treacherous. Dropping 600 feet in the short distance between two seas, characteristic of its Hebrew name Yarden meaning “descender.”[4]

Centuries later, escaping Egypt through the parted Red Sea, the fledgling Hebrew nation’s population was as “numerous as the stars of heaven.”[5] Delayed by 40 years as a punishment for unfaithfulness, it was time to return to the land of Abraham, called “the place” by God at Mt. Sinai.[6]

Entering the land, the Hebrews first had to ford the Jordan River. Normally not a big problem, flood stage is a different matter when the River is swollen to several times its width and current.

Commanded by God, the Hebrew’s were to cross the Jordan when it was flooding. Thousands of women, the aged, disabled, and young children were among the great number of people who were to cross the River.

Greatest of faith would required. Priests carrying the Ark of the Covenant touched the water of the River first commencing a great miracle.

No water flowed into the Dead Sea and the water backed up over 30 miles to the city of Adam, halfway to the Sea of Galilee.[7] All the Hebrew people crossed the riverbed on dry ground.

Joshua, the leader successor to Moses, remarked that the miracle on the Jordan was tantamount to the miracle of the parting of the Red Sea. The Bible reports that enemies of the Hebrews hearing about the miracle were struck with great fear and it took away their courage.

Hundreds of years had passed when the prophet Elijah was called by God to Jericho and then to the Jordan River. At the River’s edge, Elijah was accompanied by his protégé Elisha.

Witnessed by 50 members of the prophet society from Jericho, Elijah took off his cloak and hit the water, the waters parted, and they both walked across on dry ground. There is no mention of flooding waters on this occasion.[8]

Elisha watched as Elijah was taken away in a chariot of fire by a windstorm when his cloak to fell off. Elisha picked up the cloak, hit the waters of the Jordan and again the River parted allowing Elisha to walk back across to Jericho. The 50 members of the Jericho prophet society bowed down in awe to Elisha.

Naaman, captain of the Syrian (Aram) army, had contracted the dreaded Leprosy disease. Syria was an enemy of Israel evidenced by his wife’s servant who was a young slave girl captured from a recent conquest in Israel.

Wistfully the Jewish slave girl commented to her mistress that if only the commander could see the prophet of Samaria, he could cure her master’s disease. Naaman’s wife mentioned this to her husband who, in turn, told his King who said, “Go now, and I will send a letter to the King of Israel.”[9]

Misunderstanding the nature of the letter, the King of Israel thinking it was directed to himself tore his clothes saying, “Am I God, to kill and to make alive, that this man is sending word to me to cure a man of his leprosy? But consider now, and see how he is seeking a quarrel against me.”[10]

Elisha heard of the King’s distress and asked that Naaman be sent directly to him. With his military escort, horses and chariots, Naaman arrived at the doorstep of Elisha, but instead of coming out to greet the commander, Elisha sent out his servant telling Naaman to go wash seven times in the Jordan River.

Taking offense at the rude behavior, Naaman caustically asked why was it necessary to travel so far when there were other closer rivers which would have been better? Servants advised Naaman that it was a simple instruction…considering what it could have been…so why not try it?

Naaman reconsidered Elisha’s instructions, washed in the Jordan seven times and miraculously he was healed giving him skin as smooth as a young child. Returning to stand before Elisha, the grateful enemy military captain acknowledged the power of Jehovah and renounced the Syrian god Rimmon.[11]

Several hundred more years later, people from Jerusalem and all around Judea and the regions of the Jordan came to be baptized by John the Baptist in the Jordan River.[12] Luke referenced five historical figures to mark this specific time, consistent with secular history – the 15th year of Caesar Tiberius; procurator Pontius Pilate; Tetrarchs Herod [Antipas] of Galilee and Philip of Iturea and Trachonitis; and leaders of he Jewish priesthood, Annas and Caiaphas.[13]

John prophesied that someone more powerful than him was coming, one whom he was not even worthy to tie his sandal laces.[14] That person, Jesus of Nazareth, soon came to John to be baptized in the Jordan River.[15]

Appearing in all four Gospels, the accounts of the baptism of Jesus in the Jordan describe a voice that came from Heaven, “You are My beloved Son; in You I am well pleased.”[16] John the Baptist is later quoted in the Apostle John’s Gospel testifying to seeing a dove descending from Heaven when God spoke of Jesus, “this is the One who baptizes in the Holy Spirit.”[17]

Beginning with Abram until the arrival of Jesus of Nazareth, the Jordan River played a significant role in the history of Israel. Was it merely a coincidence the Jordan River is where Jesus of Nazareth was baptized and recognized by God?

Updated December 5, 2024.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

REFERENCES:

[1] Genesis 13:10. NIV, NRSV, NKJV. CR Genesis 13:12. CR

[2] Number 34:11-12; Deuteronomy 3:17-18, 12:10; Joshua 16:1. Deuteronomy ; Joshua 23:4.

[3] Deuteronomy 3:17. “THE LAND: Geography and Climate.” Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2013. <https://mfa.gov.il/mfa/aboutisrael/land/pages/the%20land-%20geography%20and%20climate.aspx>> “Jordan – Geography and Environment.” The Royal Hashemite Court. 2001. http://www.kinghussein.gov.jo/geo_env1.html>> “Jordan River Valley.” Encyclopædia Britannica. 2021. https://www.britannica.com/place/Jordan-Valley> “Jordan River.” Encyclopædia Britannica. 2021. <https://www.britannica.com/place/Jordan-River> “Jordan Valley.” Geography. n.d. <https://geography.name/jordan-valley> “Jordan River.” BibleHistory.com. 2020. <https://www.bible-history.com/geography/ancient-israel/jordan-river.html “Geography of Israel: The Jordan Valley.” Jewish Virtual Library. 2021. <https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-jordan-valley> NetBible.org. Footnote 2. <http://classic.net.bible.org/verse.php?book=Deu&chapter=3&verse=17#> Rogers, Lloyd Anthony. The Digital Collection of the National WWII Museum. “The Jordan River, Jericho, Israel, circa 1941-44.” photo. circa 1941-44. https://www.ww2online.org/image/jordan-river-jericho-israel-circa-1941-44>> “Jordan.” NetBible.org. Search criteria. 2021. <http://classic.net.bible.org/search.php?search=Jordan&page=1>> “Jordan River.” BiblicalTrainingLibrary.org. n.d. <https://www.biblicaltraining.org/library/jordan-river> “Jordan River.” BibleHub.com. n.d. <https://bibleatlas.org/jordan_river.htm> “Jordan River.” LifeInTheHolyLand.com. n.d. <http://www.lifeintheholyland.com/jordan_river>>

[4] “H3383.” Lexicon-Concordance Online Bible. n.d. <http://lexiconcordance.com/hebrew/3383.html></a

[5] Exodus 12:40; Deuteronomy 10:22. NASB. CR Genesis 15:13; 22:17; 26:4; Deuteronomy 1:10.

[6] Deuteronomy 11:8-15; 27:2-10.

[7] Joshua 3-4. “The Jordan River and the Baptism Site of Yardenit.” Israel Tourism Consultants. 2017. <https://www.israeltourismconsultants.com/Travel-Blog/The-jordan-river-and-the-baptism-site-of-yaardenit-in-israel> “Jordan River.” SeeTheHolyland. 2021. <https://www.seetheholyland.net/jordan-river> CR Rodriquez, Seth. “Picture of the Week: Jordan River Flooding in 1935.” BiblePlaces.com. photo. 2013. <https://www.bibleplaces.com/blog/2013/02/picture-of-week-jordan-river-flooding> “Map of Old Testament Israel – The City of Adam. Bible History. 2020. <https://www.bible-history.com/geography/ancient-israel/ot/adam.html> “Map of Old Testament Israel. Bible History. 2020. <https://www.bible-history.com/geography/ancient-israel/israel-old-testament.html>

[8] 2 Kings 2-5.

[9] 2 Kings 5:5. NASB, NKJ

[10] 2 Kings 5:7. NASB.

[11] 2 Kings 5:15-19. NetBible.org. Hebrew text.

[12] Matthew 3:6; Mark 1:5; Luke 3:23; John 1:28. CR John 3:26; 10:40.

[13] Luke 3:1-3.

[14] Luke 3:15-16; John 1:26-28.

[15] Matthew 3:13-17; Mark 1:9-13; Luke 3:21-22; John 1:29-34.

[16] Luke 3:22. NASB, NKJV. CR Matthew 3:16-17; 17:5; Mark 3:17; John 3:22.

[17] John 1:32, 34.