Reactions to the Risen Dead

According to the Gospels, Jesus of Nazareth raised three people from the dead, each under very different circumstances. Two are uniquely recounted by individual Gospel authors and one was documented by three Gospels.

No comments are recorded from those who received back their life. Instead, reactions to the risen dead came from other witnesses.

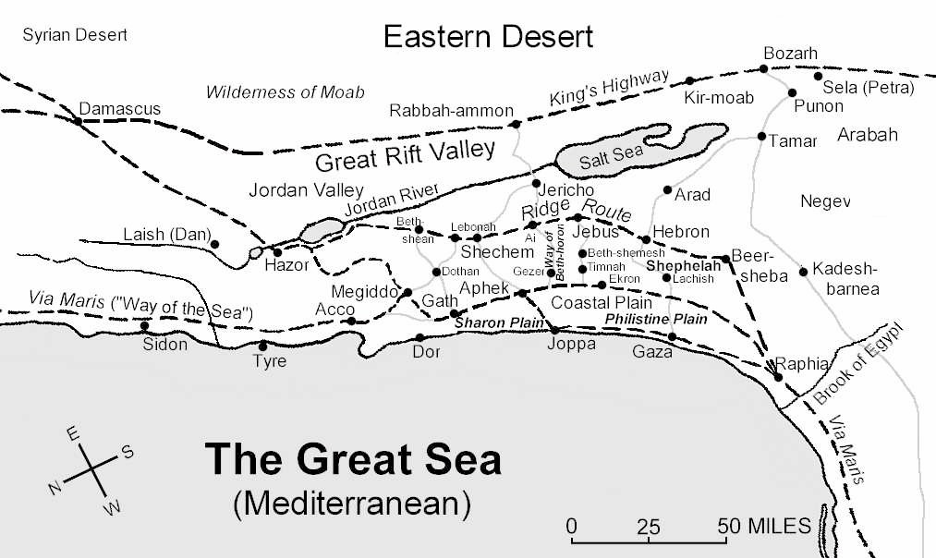

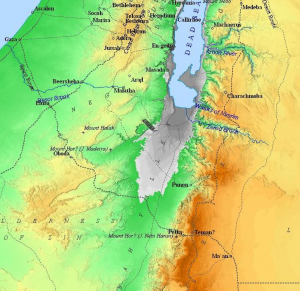

Nain was a small town a few miles southeast of Nazareth, identified by Luke.[1] Jesus was followed by his Disciples and a large throng when they encountered a long funeral procession leaving through the city gate.

Upon the funeral bier was the body of the only son of a widow. Seeing the most sad situation, Jesus felt compassion and comforted the distraught mother telling her not to cry.[2]

Touching the bier, the funeral procession stopped. Jesus commanded, “Young man, I say to you, arise!”

Sitting up, the young man began to talk and Jesus handed him back to his mother.[3] Fear struck the crowd for the miracle Jesus had performed yet they shouted praises, “A great prophet has arisen among us!” and “God has visited His people.”[4]

Crossing back across the Sea of Galilee from the region of Gerasenes after performing an exorcism on the demon named Legion, Jesus was met by a man asking to heal his dying daughter who was 12 years old.[5] Mark and Luke identify the man as a synagogue ruler named Jairus; Matthew did not identify the man by name.[6]

Along the way to the house, some people arrived to report Jairus’ daughter had died suggesting that Jesus should no longer be bothered. Hearing them, Jesus said:

Mk 5:36 “Do not be afraid; only believe.”

Arriving at the house, Jesus declared the girl was only asleep, but people derided him for saying such a thing. Everyone was sent out of the house excepting Jairus, his wife, and some followers.[7]

Taking the hand of the girl, Jesus commanded her to get up. The girl got up, began walking around the room and Jesus instructed that she be given something to eat. Jairus and his wife, were completely “astonished.”[8]

John solely chronicles one of the most famous miracles of Jesus. He had received a message from sisters Mary and Martha in Bethany, a small hamlet suburb of Jerusalem, that their brother, Lazarus, was sick.[9]

Commenting that Lazarus’ sickness would serve to glorify God, it also would serve to be the catalyst for his crucifixion. Jesus informed his Disciples that Lazarus had “fallen asleep” and wanted to go there to awaken him.[10]

Worried enemies wanted to kill him, the Disciples urged Jesus not to go. Thinking Lazarus would presumably recover on his own anyway, going to see Lazarus would be taking an unnecessary risk.[11]

Seeing the Disciples didn’t understand what he meant, Jesus plainly told them, “Lazarus is dead.” Explaining further, he must go there to give people yet another opportunity to believe.

Presently they were in another town, probably across the Jordan River east of Jericho. Jesus stayed two more days before he left for Bethany.[12]

Approaching Bethany, Jesus was met outside the village by Martha who was very upset with Jesus complaining that if he had been there earlier, her brother would not have died.Martha sent word to Mary asking her sister come out to meet Jesus, too.[13]

Mary, along with other people from their family’s house, joined Martha outside of Bethany. She candidly blamed Jesus for her brother’s death because he had not been there earlier. Some people grumbled aloud that if Jesus could heal a blind man, he certainly could have saved Lazarus.[14]

Deeply moved by the great sorrow of his friends, Jesus himself wept and went to the tomb of Lazarus. It was covered by a stone and he asked that it be removed. Martha pointed out the obvious – by now, after four days, the body of Lazarus would have the bad smell of death.[15]

Addressing the people, he told those gathered at the tomb they would now witness the glory of God. Looking toward Heaven, Jesus thanked God for the miracle he was about to perform because it would demonstrate that he was sent to them by God.

Standing outside the tomb, in a loud voice Jesus shouted, “Lazarus, come out!” Lazarus emerged from the tomb alive still wrapped and bound in the burial strips of cloth with the facial cloth over his head. Jesus told them to unwrap Lazarus to free him.

Many who believed Jesus was sent by God told others to what they had witnessed that day. Some told the Pharisees who, as clearly evidenced by their words and actions, also believed Lazarus had been raised from the dead.[16]

Pharisees worried the celebrity status of Jesus would now be even greater – the people would believe Jesus is their savior. If they didn’t do something, then Rome would take action against them for circumventing the government.

Traveling to Ephraim north of Jerusalem, the public ministry of Jesus ended with the resurrection of Lazarus.[17] Six days before the Passover, Jesus returned to Bethany for dinner when none other than Lazarus joined the dinner party.[18]

To see Jesus and Lazarus for themselves, the man who had been raised from the dead, a large group of people gathered in Bethany. When word got back to the Jewish leadership, it prompted High Priest Caiaphas to say it was better for one man to die than the entire nation.[19]

The next day, a large portion of the crowd who witnessed the event with Lazarus in Bethany greeted Jesus when he entered Jerusalem, known in Christianity as Palm Sunday.Many were still talking about the miracle of the resurrection of Lazarus.[20]

If Jesus could raise others from the dead with power granted by God, is it conceivable Jesus would then have the same power to rise from the dead himself if that power was granted by the creator of all life, God?

Updated March 14, 2025.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

REFERENCES:

[1] “Nain.” The Free Dictionary by Farlex. 2021. <https://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/Nain> “Nain.” Bible History. 2020. <https://www.bible-history.com/geography/ancient-israel/nain.html>

[2] Luke 7:13.

[3] Luke 7:14-15. NASB, NRSV, NKJV.

[4] Luke 7:16. NASB, NJKV.

[5] Mark 5:42; Luke 8:42.

[6] Matthew 9:18-26; Mark 5:21-24, 38-42; Luke 8:40-56.

[7] Mark 5:40.

[8] Mark 5:42; Luke 8:56. CR John 21:9-14; Luke 24:36-43.

[9] Bethany.” Encyclopædia Britannica. 2021. <https://www.britannica.com/place/Bethany-village-West-Bank> “Bethany.” Bible History. 2020. <https://www.bible-history.com/geography/ancient-israel/bethany.html

[10] John 10:40, 11:7-8. “ Ruark, Janet. Pinterest.com. “Jesus Is My Friend.” image. n.d. <https://i.pinimg.com/originals/96/8e/6c/968e6cbec1c37ca834062c7b1dd0f911.jpg>

[11] John 11:11-12.

[12] John 11:8, 16.

[13] John 11:1; 14.

[14] John 11:21.

[15] John 11:32 37.

[16] 1 John 11:39.

[17] John 11:45-53; 12:19.

[18] “Map of New Testament Israel.” Bible History. Map. 2020. <https://www.bible-history.com/geography/ancient-israel/israel-first-century.html> “Ephriaim.” BibleHub. n.d. <https://bibleatlas.org/ephraim.htm> “Ephraim in the wilderness.” Wikipedia. 2020. <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ephraim_in_the_wilderness>

[19] John 12:2.

[20] John 12:10 17.