Horrors of Death By Crucifixion

Jesus of Nazareth was crucified and died on the cross according to all four Gospels. In contradiction some opposing theories, including a major world religion, claim Jesus did not actually die on the cross…even if he was crucified.[1]

Crucifixion is a reality meant to kill without survivors. In addition to the four Gospel authors, others wrote of crucifixions including historian Josephus and the great Roman orator and lawyer, Cicero.

Roman capital execution by crucifixion followed a well-honed process. Horrors of crucifixion can be described in no less than graphic terms. In fact, the English word “excruciating” is derived from the word “crucify” or “crux” meaning cross.[2]

Modern medical science has corroborated the effects of a Roman scourging and crucifixion referenced by historical sources.[3] PhD level research in the fields of forensics, pathology, and modern medicine articulate the horrific impacts.[4]

First, the victim was flogged or scourged by a multi-tipped whip containing fragments of metal or bone intended to rip the flesh off the victim. It inflicted terrible pain and weakened the victim through loss of blood causing severe dehydration and thirst, induced shock, and could even lead to death before the actual crucifixion.

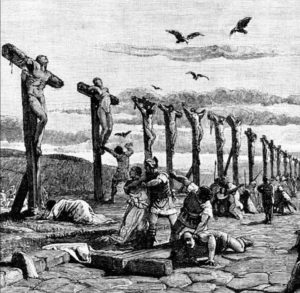

Next, it is believed the condemned were often forced to carry their own patibulum (crossbeams) weighing about 75 to 125 pounds on the long trek to a conspicuous public place of execution outside the city walls. Awaiting there were upright posts or stipes left in place, as historical evidence suggests, because of the frequency of use and scarcity of wood.

Once at the crucifixion site, the execution detail stripped off the clothing of the victims; forced down to the ground in their open wounds; and were affixed to the patibulum by nails and possibly along with ropes. The patibulum was then fitted onto the upright stipes where the job was finished by nailing their feet to the stipes.

Crucifixion victims shredded by flogging were faced with enduring a humiliating and slow death. Suffering included severe dehydration, exposure and unspeakable pain.

Each breath caused more excruciating pain, the consequence of hanging by extended arms. The victim had to push up full body weight on nailed feet which, at the same time, pulled at the nail wounds driven through nerves in the wrists.

Hypothermia would have added to the misery. Exposure was compounded by wind chill, moisture from blood and sweat, and the severe injuries inflicted by scourging and being nailed to the cross.[5]

Gospels accounts report Peter warming by a fire in the courtyard the night of the trial and the crucifixion of Jesus began in the morning around 9:00am. Considering the average 59° April temperature in Jerusalem ranging from lows as far down as 49°F to highs in the 70s°F, it was chilly.

As if the physical torture wasn’t enough, there was the mental torment of humiliation by being stripped of clothing and hanging from the cross at a high traffic location as a spectacle for staring passers-by who, along with the Roman soldiers, shouted insults at the victim. Hanging defenseless, bloodied and fully exposed on the cross, the sufferer was subject to becoming living carrion for scavenging birds.

Victims most likely died from hypovolemic shock (blood circulation complications) or a combination of other factors.[6] Death was believed to be hastened by breaking the legs of the victim such as mentioned in the Gospel accounts of the two thieves crucified with Jesus.

Roman judicial crucifixions were overseen by an execution squad consisting of a centurion, exactor mortis, and four soldiers known as a quaternion.[7] In charge of the execution, the centurion was responsible for reporting back to the governing authority when the execution had been completed.[8] Failure to complete his duty could have dire consequences – survival of a crucifixion victim was not an option.[9]

Archeological evidence of a crucifixion was found in an ancient cemetery excavated in 1968 by Vassilios Tzaferis of the Israel Department of Antiquities.[10] Pottery shards in the tomb dated to the period that followed King Herod’s dynasty up to 70 AD.

One adult male’s remains, those of “Yehohanan, the son of Hagakol,” were identified by anthropologists to have died by crucifixion, his heel bone pierced by a bent 4.5 inch nail. Remains of the olive wood cross were still attached between the nail bend and the heel bone as well as a remnant of the acacia or pistacia wooden plaque between the head of the nail and outside of the heel bone. The lower leg bones had been splintered by a sharp blow.

Forensic, pathology, and medical research; antiquity historical references; an archeological discovery and anthropology research all remarkably corroborate the circumstances of the crucifixion details in the Gospel accounts.

Considering the scientific information that substantiates historical references, how believable are the Gospel accounts saying that Jesus of Nazareth died by means of crucifixion ?

Updated September 24, 2024.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

REFERENCES:

Gospel accounts of the crucifixion of Jesus: Matthew 27:26-56; Mark 15:15-41; Luke 23:20-49; John 19:1-35.

[1] Shah, Zia. “Jesus did not die on the cross!” For Christians, To be Born Again in Islam! 2012. <https://islamforwest.org/article/jesus-did-not-die-on-the-cross rel=”nofollow”> Quran 4:157, Pickthall translation. <http://www.islam101.com/quran/QTP/index.htm > Hill, Kate, “The Physical Death of Jesus Christ: The “Swoon Theory” and the Medical Response.” 2015. Providence College. <http://digitalcommons.providence.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=faith_science_2015> Samuelsson, Gunnar. Crucifixion in Antiquity. 2011. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck. <https://www.academia.edu/4167205/Crucifixion_in_Early_Christianityrel=”nofollow”>

[2] “excruciating.” Dictionary.com. 2017. <http://www.dictionary.com> “crucifixion.” Merriam-Webster. 2017 <http://www.merriam-webster.com>

[3] Cicero. Secondary Orations Against Verres, Book 5, Chapter LXVI. Zias, Joe. Joe.Zias.com. “Crucifixion in Antiquity – The Anthropological Evidence.” 2009. Archive.org. <http://web.archive.org/web/20121211060740/http://www.joezias.com/CrucifixionAntiquity.html> Josephus, Flavius. The Life of Flavius Josephus. #75. Google Books. n.d. <http://books.google.com/books?id=e0dAAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false>

[4] Edwards, William D.; Gabel,Wesley J.; Hosmer, Floyd E. The Journal of the American Medical Association. “On The Physical Death of JesusChrist.” March 21, 1986, Volume 256 <http://hopechurchonline.net/pdf/JAMA_article_The_Crucifixion_of_Jesus_Christ.pdf> Zugibe, Frederick T., PhD. E-Forensic Medicine. “Turin Lecture: Forensic and Clinical Knowledge of the Practice of Crucifixion.” 2005. <http://web.archive.org/web/20130925103021/http://e-forensicmedicine.net/Turin2000.htm> Cilliers, L. & Retief F. P. U.S. National Library of Medicine|National Institute of Health. “The history and pathology of crucifixion.” Dec;93(12):938-41. <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14750495> Maslen and Mitchell. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. “Medical theories on the cause of death in crucifixion.” 2006. <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14750495>

[5] “Weather in April in Jerusalem.” Climatemps.com. <http://www.jerusalem.climatemps.com/april.php> “Jerusalem.” HolidayWeather.com. <http://www.holiday-weather.com/jerusalem/averages/april> McCullough, Lynne, M.D. and Arora, Sanjay, M.D. AAFP.org. 2004 Dec 15. http://www.aafp.org/afp/2004/1215/p2325.html> Li, James, M.D. “Hypothermia.” Sep 09, 2016. <http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/770542-overview#a5> “Ancient Roman “Crucifixion Spike” 1st – 2nd Century AD.” Ancient Resource. photo. 2020. <http://www.ancientresource.com/lots/roman/crucifixion-nails-spikes.html>

[6] Cilliers & Retief. “The history and pathology of crucifixion.” Zugibe. “Turin Lecture – Forensic and Clinical Knowledge of the Practice of Crucifixion.” Maslen and Mitchell. “Medical theories on the cause of death in crucifixion.” Alchin, Linda. Tribunes and Triumphs. “Roman Crucifixion.” 2008. <http://www.tribunesandtriumphs.org/roman-life/roman-crucifixion.htm> Zias. “Crucifixion in Antiquity – The Anthropological Evidence.” Champlain, Edward. Zugibe. “Turin Lecture – Forensic and Clinical Knowledge of the Practice of Crucifixion.” Geberth, Vernon J. “State Sponsored Torture in Rome: A Forensic Inquiry and Medicolegal Analysis of the Crucifixion of Jesus Christ.” 2012. Reprint: AAFS Proceedings Annual Scientific Meeting Washington, D.C. February 18-23. pp 176-177. 2008. <https://r.search.yahoo.com/_ylt=AwrNZs.XOMplcmMnC3wPxQt.;_ylu=Y29sbwNiZjEEcG9zAzEEdnRpZAMEc2VjA3Ny/RV=2/RE=1707780375/RO=10/RU=http%3a%2f%2fwww.practicalhomicide.com%2fResearch%2fRome2012.doc/RK=2/RS=c4KuoiEJ.qGr7k28di3AscjU6i0-> Champlain, Edward. Nero. Harvard University Press. p 1222009. <https://books.google.com/books?id=30Wa-l9B5IoC&lpg=PA122&ots=nw4edgV_xw&dq=crucifixion%2C%20tacitus&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false> Champlain, Edward. Nero. Harvard University Press. p 122. 2009. <https://books.google.com/books?id=30Wa-l9B5IoC&lpg=PA122&ots=nw4edgV_xw&dq=crucifixion%2C%20tacitus&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false>

[7] Zugibe. “Turin Lecture – Forensic and Clinical Knowledge of the Practice of Crucifixion.

[8] Santala, Risto. The Messiah In The New Testament In The Light Of Rabbinical Writings. Trans. William Kinnaird. “Jesus Before The Representatives of the Roman State.” 1993. <http://www.kolumbus.fi/risto.santala/rsla/Nt/index.html> Swete, Henry Barclay. The Gospel According to St. Mark, The Greek Text with Notes and Indices. 1902. Google Books. <https://books.google.com/books?id=WcYUAAAAQAAJ&lpg=PA127&ots=f_TER300kY&dq=Seneca%20centurio%20supplicio%20pr%C3%A6positus&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false>

[9] Seneca, Lucius Annaeus. “Seneca’s Essays Volume I.” Moral Essays. Book III. “To Novatus on Anger+.” Book I. The Stoic Legacy to the Renaissance. <http://www.stoics.com/seneca_essays_book_1.html#ANGER1> Josephus, Flavius. Wars of the Jews. Book VI, Chapter IV, Chapter VII. Google Books. n.d. <http://books.google.com/books?id=e0dAAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false> Shimron, Aryeh. The U.S. Sun. 2022. photo. Last accessed 12 Sept. 2022. <https://www.the-sun.com/news/1672868/nails-crucify-jesus-fragments-bone/#>

[10] Shanks, Hershel. “Crucifixion Bone Fragment, 21 CE.” The Center for Online Judaic Studies. 2004. <http://cojs.org/crucifixion_bone_fragment-_21_ce> Tzaferis, Vassilios. Bible Archaeology Society. “Crucifixion – the Archaelogical Evidence.” n.d. <https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-topics/crucifixion/a-tomb-in-jerusalem-reveals-the-history-of-crucifixion-and-roman-crucifixion-methods>