Preparation Day – Did John Contradict Himself?

Preparation Day is mentioned several times in the Gospels, but two verses in John seem to create a conflict. Some critics point to these two Preparation Day references in John to claim a Gospel contradiction exists thereby casting doubt on the integrity of Gospel accounts about Jesus of Nazareth.[1]

Does John contradict himself within just 16 verses? In the first reference, Pilate was judging Jesus:

JN 19:14 “Now it was the Preparation Day of the Passover, and about the sixth hour. And he said to the Jews, “Behold your King!”” (NKJV)

In this scenario, “Preparation Day” seems to have preceded the Passover because it implies Jesus was judged by Pilate before the Feast of Unleavened Bread. If true, this view would be conflicting with John’s own second reference to the “Preparation Day” preceding the Sabbath a few verses later:

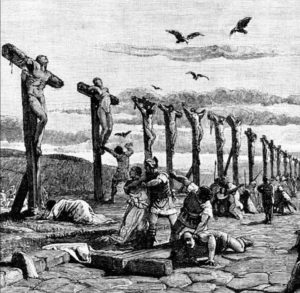

JN 19:31 “Therefore, because it was the Preparation Day, that the bodies should not remain on the cross on the Sabbath (for that Sabbath was a high day), the Jews asked Pilate that their legs might be broken, and that they might be taken away.” (NKJV)

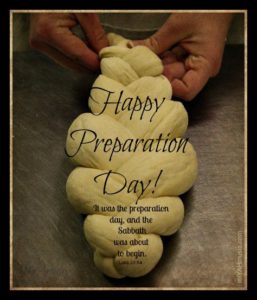

Scriptures define the time when the Hebrew people “prepared” the day before the Sabbath, traditionally called the “Preparation Day.”[2] After escaping Egypt, God set an example of this preparation by providing the Hebrews in the desert twice the amount of manna on the sixth day, but nothing on the seven day.[3]

Scriptures define the time when the Hebrew people “prepared” the day before the Sabbath, traditionally called the “Preparation Day.”[2] After escaping Egypt, God set an example of this preparation by providing the Hebrews in the desert twice the amount of manna on the sixth day, but nothing on the seven day.[3]

Ex 16:22-23 Now on the sixth day they gathered twice as much bread, two omers for each one…”This is what the LORD meant: Tomorrow is a sabbath observance, a holy sabbath to the LORD. Bake what you will bake and boil what you will boil, and all that is left over put aside to be kept until morning.”

Occam’s Razor theory suggests that the simplest explanation is usually the right one. While preparing for the Sabbath is spelled out in Exodus, several clues can be found within these two verses and God’s Law.

Three Festival holy days were also to be regarded as a Sabbath, an “appointed time.” Only the Passover was to be observed on a specific day, Nisan 15.[4]

Greek text uses the word paraskeuh meaning “preparation” further defined as “the day of preparation, the day before the Sabbath, Friday.”[5] In most English Bible versions, John 19:14 is translated as “… for the Passover” while others say “… of the Passover.”

John 19:31 has a parenthetical comment, “for that Sabbath was a high day.” The original Greek word for “high” is megas meaning “great,” yet out of 44 translations only 15 versions translate the word as “great,” none of which are the mainstream versions.[6]

Another clue is the Greek text word sabbaton, the Sabbath, where there is no other meaning. Defined in the Law of Moses, God’s commandment said the weekly Sabbath is a holy day prohibiting “all manner of work.”[7]

Prohibitions of work ran the gambit from cooking, drawing water, walking, carrying, making fires, feeding livestock, harvesting, etc. To avoid such violations, preparatory work for these tasks had to be completed before sunset Friday evening – the day of preparation for the Sabbath. The Talmud expounded on the meaning by detailing what was or was not considered “work” – rules notoriously enforced by the Pharisees.

Customarily on the first day of Passover, Nisan 15, people were busy with other religiously required and traditional activities. Every year Nisan 15 fell on a different day of the week and when it fell on a Friday, it created a back-to-back Sabbath scenario presenting a legal conundrum.

According to the Talmud’s interpretation of the Law, people were meant to “enjoy” the Passover Festival. Confounded by the strict weekly Sabbath restrictions, the enjoyment factor for a Friday Passover seemed to be greatly diminished.

In a back-to-back Sabbath scenario, it would actually be a hardship to require the people to abide by two days of strict Sabbath work restrictions for Friday and Saturday, not to mention farming activities.

Festival Sabbath language in the Law of Leviticus and Numbers used the Hebrew word abodah meaning “labor” that was interpreted by Rabbi Sages to be a more lenient work restriction than the weekly Sabbath of “all manner of work.” English translations reflect this difference saying “servile work,” “laborious work,” “regular work,” “occupations” and “customary work.”[8]

When Nisan 15 fell on a Friday Sabbath Preparation Day, it was considered to be a special day when the Sabbath work restrictions were somewhat relaxed. In the spirit of the Passover intended by God to be a celebratory festival, the Babylonian Talmud addressed the scenario.[9]

“The general purpose underlying these laws is to enhance the joy of the festival, and therefore the Rabbis permitted all work necessary to that end, while guarding against turning it into a working-day.” – Jewish Encyclopedia [10]

Wading through the analysis of Greek text clues, the Talmud and the Bible’s definition of the preparing for the Sabbath, Johns two references refer to the same “preparation day,” but under two different scenarios:

Verse 14 is in the context of an event marking the specific day when Pilate presented Jesus to the crowd that morning, “the Preparation Day of the Passover.”

Verse 31 is in the narrower context of the very same day. The imminent sunset would begin the weekly Sabbath and its much stricter rules – “because it was the Preparation Day, that the bodies should not remain on the cross on the Sabbath.” It is the reason Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus were in a hurry to bury the body of Jesus before sunset.

Do the two references in John to the “preparation day” create a Bible contradiction?

Updated November 14, 2023.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

REFERENCES:

Gospel references: Matthew 28, Mark 16; Luke 24, John 20.

[1] Wells, Steve. The Skeptic’s Annotated Bible. 2017. “423. When was Jesus crucified?” http://skepticsannotatedbible.com/contra/passover_meal.html rel=”nofollow”</a> “101 Bible Contradictions.” Islamic Awareness. n.d. Contradiction #69. <http://www.islamawareness.net/Christianity/bible_contra_101.html rel=”nofollow”</a>

[2] Exodus 16:22-23, 29. Edersheim, Alfred. The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah. 1883. Book V, Chapter 15, pp 1382-1392 & pp 1393-1421. <http://philologos.org/__eb-lat/default.htm> Edersheim, Alfred. The Temple – Its Ministry and Services. Chapter 10. 1826 -1889. The NTSLibrary. 2016. “Happy Preparation Day.” Gail-Friends. image. 2017. <https://3.bp.blogspot.com/-qEj69N9z6bM/WR87uOnqzcI/AAAAAAAAkvI/hcScRQ40VasvaY1QHdF7bI3C4ep9rsanACLcB/s1600/sabbath%2Bprep.jpg><http://www.ntslibrary.com/PDF%20Books/The%20Temple%20by%20Alfred%20Edersheim.pdf> “Happy Preparation Day.” Gail-Friends. image. 2017. <https://3.bp.blogspot.com/-qEj69N9z6bM/WR87uOnqzcI/AAAAAAAAkvI/hcScRQ40VasvaY1QHdF7bI3C4ep9rsanACLcB/s1600/sabbath%2Bprep.jpg>

[3] Exodus 20:8-10, 31:15; Leviticus 23:3. “G4521.” Lexicon-Concordance. n.d. <http://lexiconcordance.com/greek/4521.html> BibleHub.com. Parallel. <https://biblehub.com/john/19-31.htm> CR Exodus 16:23-26; Mark 15:42.

[4] Exodus 23:14-19; Leviticus 23:1-8. “Festivals,”“Holy Days,” “Passover,” ”Shabbat.” Jewish Encyclopedia. 2011. <http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com> “The Three Annual Feasts of God.” BibleView.org. n.d. <https://bibleview.org/en/bible/moses/3feasts/. Babylonian Talmud. Rodkinson. Book 1, Tract Sabbath, Chapters 1-10.”Sabbath.” Jewish Encyclopedia. 2011. https://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/6359-friday “Sabbath and Sunday.” Jewish Encyclopedia. 2011. <https://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/14115-sunday-and-sabbath Babylonian Talmud. Rodkinson trans. Sabbath, Book 1, Chapter I; Book 2; Erubin, Pesachim, Book 3, Chapter IV, VI, VIII. 1918. <https://www.sacred-texts.com/jud/talmud.htm#t03 Soncino Babylonian Talmud. “Shabbath.” <https://israelect.com/Come-and-Hear/shabbath/index.html>

[5] John 19:14. NetBible.org. Greek text. n.d. <https://classic.net.bible.org/verse.php?book=Joh&chapter=19&verse=14> “G3904.” Lexicondordence.com. n.d. <http://lexiconcordance.com/greek/3904.html>

[6] John 19:31. Netbible.org. n.d. Greek text. n.d. <https://classic.net.bible.org/strong.php?id=3173> “G3173.” Lexicon-Concordance. n.d.<http://lexiconcordance.com/greek/3173.html>

[7] Netbible.org. n.d. Hebrew text. “H4399.” Lexicon-Concordance. n.d. <http://lexiconcordance.com/hebrew/4399.html> CR Exodus 31:15, 35:2.

[8] Leviticus 23:7-8; Numbers 28:18. Net.Bible.org. Hebrew text, footnote #20. CR Exodus 23:14. Netbible.org. n.d. Hebrew text. “G5656.” Lexicon-Concordance. n.d. <http://lexiconcordance.com/search6.asp?sw=5656&sm=0&x=0&y=0>

[9] Babylonian Talmud. Rodkinson trans. Book 3, Tracts Pesachim, Chapter IV and Book 4, Tract Betzah (Yom Tob); Book 4, Tract Moed, Chapter II.. <https://www.sacred-texts.com/jud/talmud.htm#t03> KJV, NET, NIV, NASB, NLT, NRSV, NKJV. Special Shabbots.” Jewish Virtual Library 2008. <https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/special-shabbats> “Special Sabbaths.” TorahResource. n.d. <https://torahresource.com/resources/weekly-parashah/special-readings/special-sabbaths/> Posner, Menachem. Chabad.org. “13 Special Shabbats on the Jewish Calendar.” 2019. <https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/4333597/jewish/13-Special-Shabbats-on-the-Jewish-Calendar.htm>

[10] “Holy Days.” Jewish Encyclopedia. 2011. <https://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/7814-holidays>