Matthew – Uniqueness Among the Gospels

Matthew’s Gospel is surrounded by many questions – who, when, what, how – making it a target rich environment for those who wish to challenge its credibility. Parallel passages, dates, authorship and variation from other Gospels are all called into question.

Much of the details of the ministry of Jesus of Nazareth are found only in Matthew. Less than a third of Matthew’s content is common to Mark. Slightly more than a third of the content of Matthew is not in common with Luke … Matthew’s subject matter is in many ways unique.[1]

Variation actually enhances the authenticity and credibility of Matthew. In the world of investigations, written statements that too closely resemble each other are immediately suspect of deception.[2]

Truthful, credible statements are expected to be consistent with key evidence as well as with other witness statements, yet characteristic variation is most certainly expected. A basic investigative principal: the more details, the harder to cover a deception; conversely, a deceptive statement lacks details making it more difficult to validate.

“There must, therefore, naturally arise great differences among writers, when they had no original records to lay for their foundation, which might at once inform those who had an inclination to learn, and contradict those that would tell lies…” – Josephus [3]

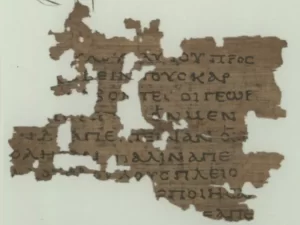

Distinct diversity from Luke can be seen immediately in Matthew with the genealogy of Jesus listed in reverse order along with some generational variations.[4] Three miracles and at least 10 parables found in Matthew do not appear in any other Gospel.[5]

Joseph‘s personal circumstances are told only in Matthew such as his contemplation of divorcing Mary for becoming pregnant by another man. His mind was changed by an angel’s visitation message that Mary’s childbirth would fulfill the Isaiah 7:14 prophecy of a virgin birth and instructed Joseph to name the baby “Jesus.”

Any question about “Bethlehem of Judea” being the birthplace of the Messiah was addressed by Herod’s own Jewish religion experts. Herod asked where Christos could be found and they cited the Micah 5:1/2 prophecy.

Exclusive to Matthew are the unusual circumstances of the mystic Magi; their astronomy perspective; King Herod’s treachery and the King’s death shortly after the birth of Jesus. Details of Herod’s chaotic final days are described by historian Josephus.

Combined with Luke’s Nativity account, Matthew’s historical and astronomy attributions raises the bar of Gospel answerability to the highest degree.

Established is a narrow timeline window for the birth of Jesus with five date markers – the rules of Augustus, Herod, and Quirinius; a Roman Empire registration plus “his Star.” The Gospel also names secular historical figure Archelaus, Herod’s son, who ruled in Judea after the King died.[6]

Literary analysis and literary criticism are among important scientific methodologies used to assess credibility.[7] Integrity of the Gospel alone can be evaluated entirely based on assessing just its content.

One of the most famous teachings of Jesus, unique to Matthew, is the famed “Sermon on the Mount” including nine verses of Beatitudes, all beginning with “Blessed are…” Covering 106 verses through three chapters, the sermon’s details required an eyewitness.[8]

Perhaps the biggest clue from Matthew to the divine nature of Jesus is from his personal perspective as One who watched Jerusalem throughout its history. The author of Luke chose to include Matthew’s quoted statement of Jesus in his own investigative report:[9]

MT 23:37 “O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, the one who kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to her! How often I wanted to gather your children together, as a hen gathers her chicks under her wings, but you were not willing!” (NKJV)

Moving to the crucifixion, burial and the Resurrection, Matthew solely recounts details surrounding the death of Jesus. Described by the Gospel are an earthquake, stones split in two, and tombs being opened with bodies coming back to life.[10]

Precluding several conspiracy claims, Matthew uniquely describes the chain of custody over the body of Jesus – the crucifixion by Rome; burial by a member of the Jewish Council; the Jewish leadership’s request for Pilate to secure the tomb exclusively using the Greek word koustodia; and the early morning events of Sunday.[11]

Morning of the Resurrection, Matthew includes the lone accounts of several key happenings – the angel rolling away the stone from the empty tomb; the earthquake; the proclamation of the angel; dereliction of the Guards and their report to the chief priests. Later that same day, Matthew includes the resurrected appearance of Jesus to women of Galilee.

Use of common reference materials evidenced by the parallel passages, sometimes verbatim, appears in all three synoptic Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke.[12] Parallel passages cited as alleged credibility issues can be attributed to legitimate literary protocols of the day.

Copying from another source to serve as a “witness” was a respected form of citation and corroboration. It was common practice to copy from another source, even verbatim, without a citation. Abuses of this practice by the Greeks were the focus of Josephus in his work, Against Apion.[13]

Authorship of Matthew is not claimed within the Gospel itself. Not penning a work was characteristic Jewish practice for reasons of humility, to avoid bringing fame or attention to the author. Examples of other Jewish works without authorship or a formal identify are the authors of books within the Old Testament, the Tenakh.[14]

Customarily Matthew is believed, based on sources who lived in very close time proximity, to have been written by one of the 12 Disciples of Jesus for whom the Gospel is named – an eyewitness account.[15] Other scholars and skeptics with differing views believe Matthew was written by someone else; is a collection of stories and oral traditions; or is even completely fictitious.[16]

Which was written first, Mark or Matthew, is debatable although clearly Matthew is much longer with much more detail. Many religion authorities believe Matthew was written sometime between 55-75 AD; others view the date range from 90-100 AD.[17]

Both Gospel timeframe possibilities are during the first century when some of the original Disciples were still alive as were probably some from the Sanhedrin who lived at the same time as Jesus of Nazareth. If any details of the information was found to be untrue, no evidence from these contemporaries refutes it.

Portions of Matthew were corroborated by the eyewitness account of John’s Gospel written independently from his prison cell; Luke’s investigative Gospel; and secular history.[18] Considering the customary literary protocols, the allegation of literary misconduct is rendered to be a non-issue.

What remains to assess the credibility of Matthew is its believability. Are the Gospel’s detailed accounts fabrications… or do the unique details in Matthew indicate truthfulness and credibility?

Updated October 9, 2024.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

REFERENCES:

[1] “Matthew.” Easton’s 1897 Bible Dictionary. n.d. <http://www.ccel.org/e/easton/ebd/ebd/T0002400.html#T0002442> “Luke.” Easton’s 1897 Bible Dictionary. n.d. <http://www.ccel.org/e/easton/ebd/ebd/T0002300.html#T0002331> Carr. The Gospel Acco rding to Matthew, Volume I. pp XVIII – XIX. Gloag, Introduction to the Synoptic Gospels. p 32-33, 38-42. Sween, Don and Nancy. “Parable.” BibleReferenceGuide.com. n.d. <http://www.biblereferenceguide.com/keywords/parable.html> Swete. The Gospel According to St. Mark, 1902. p XVII, XXIV. Fairchild, Mary. “37 Miracles of Jesus.” ThoughtCo. 2017. <https://www.thoughtco.com/miracles-of-jesus-700158> Ryrie Study Bible. Ed. Ryrie Charles C. Trans. New American Standard. 1978. “The Miracles of Jesus.” Aune, Eilif Osten. “Synoptic Gospels.” Bible Basics. 2013. <www.bible-basics-layers-of-understanding.com/Synoptic-Gospels.html> “Matthew. Easton’s Bible Dictionary. 1897. <http://www.ccel.org/e/easton/ebd/ebd/T0002400.html#T0002443> Swete. The Gospel According to St. Mark, The Greek Text with Notes and Indices. p. XXIV. Gloag, Introduction to the Synoptic Gospels. p. 33 <https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=chi.090193322;view=1up;seq=25>

[2] Sapir, Avinoam. LSI Laboratory for Scientific Interrogation. Basics and advance courses. <http://www.lsiscan.com/id37.htm> “Scientific Content Analysis (SCAN).” Personal Verification LTD. 2018. <http://www.verify.co.nz/scan.php>

[3] Josephus, Flavius. The Complete Works of Josephus. “Against Apion.” 1850. Book I.5. <http://books.google.com/books?id=e0dAAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false>

[4] Matthew 1; Luke 3. Irenaeus of Lyons. Against Heresies. Book III. Chapter I.1, IX, XXI.3. Ante-Nicene Fathers. Volume I. n.d. <http://www.ccel.org/search/fulltext/Heresies> “New Testament – Historical Books.” Jewish Encyclopedia. Gloag, Introduction to the Synoptic Gospels. pp ix, 39. “PAPYRUS 104 P104 (P. Oxy. 4404) A Very Early Greek Fragment Copy of the Gospel of Matthew.” Christian Publishing House Blog. image. n.d. <https://christianpublishinghouse.co/2020/07/25/papyrus-104-p104-p-oxy-4404-a-very-early-greek-fragment-copy-of-the-gospel-of-matthew>

[5] Carr. The Gospel Accouding to Matthew. Volume I. pp XVIII – XIX. Gloag, Introduction to the Synoptic Gospels. pp 32-33. Gloag, The Synoptic Gospels. pp 38-42. Smith, Barry D. “The Gospel of John.” F. 5.3.3. 2015. <http://www.mycrandall.ca/courses/NTIntro/John.htm> Sween. “Parable.” Swete. The Gospel According to St. Mark. pp. XIX, XXIII. d<https://books.google.com/books?id=WcYUAAAAQAAJ&lpg=PA127&ots=f_TER300kY&dq=Seneca%20centurio%20supplicio%20pr%C3%A6positus&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false> “Luke.” Easton’s 1897 Bible Dictionary. “Parable.” International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. 2018. <http://www.internationalstandardbible.com/P/parable.html> “The Parables of Jesus.” Ryrie Study Bible. “The Miracles of Jesus.” Ryrie Study Bible. Fairchild, Mary. “37 Miracles of Jesus.” ThoughtCo. 2017. <https://www.thoughtco.com/miracles-of-jesus-700158>

[6] Matthew 2; CR Luke 1.

[7] Carr, Frazier. The Gospel Accouding to Matthew. Volume I. p XVIII – XIX. <http://books.google.com/books?id=ZQAXAAAAYAAJ&dq=Swete%2C%20The%20Gospel%20According%20to%20St.%20Matthew&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q=Swete,%20The%20Gospel%20According%20to%20St.%20Matthew&f=false> Gloag, Introduction to the Synoptic Gospels. p 5. <http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008728595> “Gospel of Matthew.” Theopedia.com. “Jesus.” “The Book of Matthew.” Quartz Hill School of Theology. Mareghni, Pamela. “Different Approaches to Literary Criticism.” 2014. <http://web.archive.org/web/20140628042039/http://www.ehow.com/about_5385205_different-approaches-literary-criticism.html> Preble, Laura. “Traditional Literary Criticism.” 2014. <http://www.ehow.com/info_8079187_approaches-literary-criticism.html>

[8] Matthew 5-7. CR Luke 6:20-22.

[9] Mathew 24; Luke 13:34.

[10] Matthew 27.

[11] Net.bible.org. Matthew 27:65. Greek text. “koustodia <2892>.” Lexicon-Concordance Online Bible. n.d. <http://lexiconcordance.com/greek/2892.html>

[12] Fausset, Andrew R. Fausset Bible Dictionary. 1878. “New Testament.” <http://classic.studylight.org/dic/fbd/view.cgi?number=T2722>

[13] Josephus. Against Apion. Book I.1-2, 4-6, 10, 17, 19, 23, 26. Josephus. The Complete Works of Josephus. “Antiquities of the Jews.” 1850. “Preface.” Reed, Annette Yoshiko. Pseudepigraphy, Authorship, and ‘The Bible’ in Late Antiquity. 2008. p 478. <http://www.academia.edu/1610659/_Pseudepigraphy_Authorship_and_the_Reception_of_the_Bible_in_Late_Antiquity> “Custom Cheating and Plagiarism essay paper writing service.” ExclusivePapers.com. n.d. <http://exclusivepapers.com/essays/Informative/cheating-and-plagiarism.php> Cummings, Michael J. “Did Shakespeare Plagiarize?” Cummings Study Guides. 2003. <http://cummingsstudyguides.net/xPlagiarism.html>

[14] Reed. Pseudepigraphy, Authorship, and ‘The Bible’ in Late Antiquity. p 476-479. “Hebrew Bible: Torah, Prophets and Writings.” MyJewishLearning.com. <https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/hebrew-bible> Benner, Jeff, Ancient Hebrew Research Center. 2018. “The Authors of the Torah.” <http://www.ancient-hebrew.org/articles_authors.html>

[15] Luke 13:34. Luke 13:34. Papias. “Papias.” Fragment I & VI. <http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf01.vii.html> Gloag, Paton James. Introduction to the Synoptic Gospels. p 168. <https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=chi.090193322;view=1up;seq=25> Irenaeus of Lyons. Against Heresies. Book III, Chapter I.1, IX, XXI.3. <http://www.ccel.org/search/fulltext/Heresies> Swete. The Gospel According to St. Mark, 1902. p XIX. <https://books.google.com/books?id=WcYUAAAAQAAJ&lpg=PA127&ots=f_TER300kY&dq=Seneca%20centurio%20supplicio%20pr%C3%A6positus&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false>

[16] Fausset, Andrew R. Fausset Bible Dictionary. 1878. “Matthew, The Gospel According to.” <http://classic.studylight.org/dic/fbd/view.cgi?number=T2722> Didymus, John Thomas. “The Biblical Evidence For a Conspiracy Theory of the Resurrection.” 2010. <http://ezinearticles.com/?The-Biblical-Evidence-For-a-Conspiracy-Theory-of-the-Resurrection&id=4205050> “New Testament – Historical Books.” Jewish Encyclopedia. 2011. <http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/11498-new-testament> Smith, Ben C. The Synoptic Project. 2018. <http://www.textexcavation.com/synopticproject.html> Gloag, Introduction to the Synoptic Gospels. pp. 4-5, 48, 63-64, 106-108. “Gospel of Matthew.” Theopedia.com. “The Lives.” Quartz Hill School of Theology. “New Testament – Historical Books.” Jewish Encyclopedia. 2011. <http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/11498-new-testament> Kirby, Peter. “Gospel of Matthew.” EarlyChristianWritings.com. 2018. <http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/matthew.html> Vick, Tristan D. “Dating the Gospels: Looking at the Historical Framework.” Carr, A. The Gospel According to Matthew, Volume I. 1881. pp XVIII – XIX. Smith, B. D. “The Gospel of Matthew.”

[17] “Gospel of Matthew.” Theopedia.com. n.d. <https://www.theopedia.com/gospel-of-matthew> “The Lives.” Quartz Hill School of Theology. n.d. <http://www.theology.edu/biblesurvey/matthew.htm> Vick, Tristan D. “Dating the Gospels: Looking at the Historical Framework.” Advocatus Atheist. 2010. <http://advocatusatheist.blogspot.com/2010/01/dating-gospels-looking-at-historical.html> Shamoun, Sam. “The New Testament Documents and the Historicity of the Resurrection.” Answering-Islam.org. 2013. <http://www.answering-islam.org/Shamoun/documents.htm> Kirby, Peter. Index. EarlyChristianWritings.com. 2018. <http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/index.html> Smith, Barry. D. “The Gospel of Matthew.” n.d. <http://www.mycrandall.ca/courses/NTIntro/Matt.htm> Etinger, Judah. Foolish Faith. Chapter 6. 2012. <http://www.foolishfaith.com/book_chap6_history.asp> Shamoun, Sam. “The New Testament Documents and the Historicity of the Resurrection.” 2013. <http://www.answering-islam.org/Shamoun/documents.htm>

[18] Smith, Barry D. “The Gospel of John.” “The Book of John.” Quartz Hill School of Theology. “Gospel of John.” Theopedia.com. “Gospel of John Commentary: Who Wrote the Gospel of John and How Historical Is It?” Biblical Archeology Society. 2019. https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-topics/new-testament/gospel-of-john-commentary-who-wrote-the-gospel-of-john-and-how-historical-is-it/>