Cicero’s Prosecution of Murder By Crucifixion

Crucifixion is as closely associated with the image of Jesus of Nazareth as any other save perhaps the Nativity manger scene. Still, some dispute Rome’s execution of Jesus by nailing him to a cross.[1]

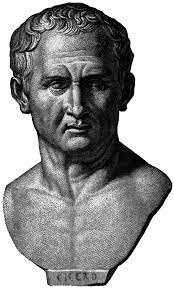

Cicero, commonly regarded as the greatest orator in Roman history, was a Senator and Consul who lived about 100 years before Pontius Pilate was Procurator of Judea.[2] A lesser known fact is that Cicero was a prosecutor, a Roman lawyer.

Secondary Orations Against Verres written by Cicero narrates his prosecution of Verres charged with premeditated murder by crucifixion of a noble Roman citizen, Publius Gavius.[3] Motive of the murder was punishment for Gavius who publicly crusaded for freedom and citizenship.

Directed squarely at Verres, the prosecutorial words of Cicero delineates the crucifixion process Verres used to kill Gavius:[4]

“…according to their regular custom and usage, they had erected the cross behind the city in the Pompeian road…you chose that place in order that the man who said that he was a Roman citizen, might be able from his cross to behold Italy and to look towards his own home?… for the express purpose that the wretched man who was dying in agony and torture might see that the rights of liberty and of slavery were only separated by a very narrow strait, and that Italy might behold her son murdered by the most miserable and most painful punishment appropriate to slaves alone.

It is a crime to bind a Roman citizen; to scourge him is a wickedness; to put him to death is almost parricide. What shall I say of crucifying him? So guilty an action cannot by any possibility be adequately expressed by any name bad enough for it…that you exposed to that torture and nailed on that cross…He chose that monument of his wickedness and audacity to be in the sight of Italy, in the very vestibule of Sicily, within sight of all passersby as they sailed to and fro.”

“…it was the common cause of freedom and citizenship that you exposed to that torture and nailed on that cross.“[5]

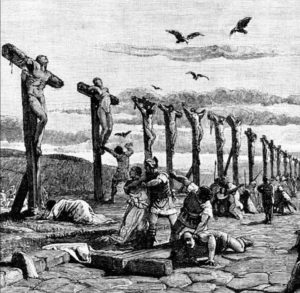

Scourging whips and a cross were the murder weapons – death by crucifixion, consistent with today’s medical science finding of injuries inflicted by a crucifixion. Humiliation, psychological and mental anguish were part of the excruciating, long lasting torment and death of Gavius.

Crucifixion was a manner of execution reserved only for slaves at that time in Roman history. Verres was allowed to self-exile to Massalia in southern France, then sentenced in abstentia to merely an undisclosed fine.

All four Gospels record that Jesus of Nazareth was scourged, nailed to a cross and killed by crucifixion. Gory specifics of a crucifixion are described in limited detail for one very simple reason – it was not necessary.

“Tacitus (“Annales,” 54, 59) reports therefore without comment the fact that Jesus was crucified. For Romans no amplification was necessary.” – Jewish Encyclopedia

Not even Roman historians Josephus, Tacitus or Suetonius found it necessary to explain crucifixion.[7] Just about everyone living in the Roman Empire knew about crucifixion – shouting out “crucify him!” the rowdy Jewish crowd at Pilate’s judgement of Jesus certainly knew about it.[6]

Seneca the Younger was born in Spain, educated in Rome, and became a stoic philosopher, statesman and dramatist with a penchant for including horror scenes in his tragedies. His life corresponded virtually with the same years as Jesus of Nazareth.

“Dialogue” is another name for a letter written by Seneca for which he is known to have written several. In the Dialogue To Marcia on Consolation, Seneca used a metaphor of crucifixion to his embittered friend who had been grieving three years over her son’s death.[8]

Obviously familiar with the gruesome realities of crucifixion, the letter suggests he expected Marcia to be familiar with it. Describing the mental anguish of people of virtue striving to overcome their own self-imposed tribulations, he wrote:

“Though they strive to release themselves from their crosses those crosses to which each one of you nails himself with his own hand – yet they, when brought to punishment, hang each upon a single gibbets [sic]; but these others who bring upon themselves their own punishment are stretched upon as many crosses as they had desires….”[9]

Generally, a “gibbet” is believed to be a gallows-like structure or an upright pole typically used to hang executed victims’ bodies by chains or ropes for public display as a method of scorn. By comparison, crucifixion involved living victims who were “stretched” out and nailed to crosses.[10]

Jewish historian Josephus personally witnessed crucifixions initially used by Rome to punish such crimes as robbery and insurrection. Eventually crucifixions, he wrote, devolved to the point of becoming Roman sport.[11]

Jewish historian Josephus personally witnessed crucifixions initially used by Rome to punish such crimes as robbery and insurrection. Eventually crucifixions, he wrote, devolved to the point of becoming Roman sport.[11]

Nine references to Roman crucifixion are made by Josephus in which no Jew was safe. In one, he wrote of crucifixions by Procurator Florus and in another from his own eyewitness perspective during the siege of Jerusalem in 70 AD:[12]

“…for Florus ventured then to do what no one had done before, that is, to have men of the equestrian order whipped and nailed to the cross before his tribunal; who although were at birth Jews, yet were they of Roman dignity notwithstanding.”[13]

“So the soldiers, out of the wrath and hatred they bore the Jews, nailed those they caught, one after one way, and another after another, to the crosses, by way of jest, when their multitude was so great, that room was wanting for the crosses, and crosses wanting for the bodies.”[14]

Are the Gospels credible in saying that Roman crucifixion by being nailed to a cross was the means used to kill Jesus?

Updated May 12, 2025.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

REFERENCES

[1] “Jesus did not die on cross, says scholar.” The Telegraph. n.d. <http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/religion/7849852/Jesus-did-not-die-on-cross-says-scholar.html rel=”nofollow” rel=”nofollow”> Warren, Meredith J.C. “Was Jesus Really Nailed to the Cross?” The Conversation. 2016. <https://theconversation.com/was-jesus-really-nailed-to-the-cross-56321 rel=”nofollow”> Perales, Ginger. “Was Jesus Nailed or Tied to the Cross?” 2016. <http://www.newhistorian.com/jesus-nailed-tied-cross/6161 rel=”nofollow”>

[2] Linder, Douglas O. Imperium Romanun. “The Trial of Gaius (or Caius) Verres.” 2008. <http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/Verres/verresaccount.html> Bunson, Matthew. Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire. “Cicero; Cicero, Marcus Tillius.” <https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780816045624>

[3] Cicero, Marcus Tullius. “The Fifth Book of the Second Pleading in the Prosecution against Verres.” Ed. Crane, Gregory R. <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0018%3Atext%3DVer.%3Aactio%3D2%3Abook%3D5>

[4] Greenough, James. B.; Kittredge, George; eds. Select Orations and Letters of Cicero. 1902. Introduction I. Life of Cicero. VII. “From the Murder of Caesar to the Death of Cicero.” <http://books.google.com/books?id=ANoNAAAAYAAJ&pg=PR1#v=onepage&q&f=false> Quintilian, Marcus Fabius. Quintilian’s Institutes of Oratory. 1856. Book 8, Chapter 4. Rhetoric and Composition. 2011. <http://rhetoric.eserver.org/quintilian/index.html> “Crucifixion.” JewishEncyclopedia.com < http://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/4782-crucifixion > “Trial of Gaius Verres – governor of Sicily.” Imperium Romanun. 2021. <https://imperiumromanum.pl/en/article/trial-of-gaius-verres-governor-of-sicily/> Linder. “The Trial of Gaius (or Caius) Verres.” Sack, Harald. SciHi Blog. “Marcus Tullius Cicero – Truly a Homo Novus.” image. 2020. <https://www.google.com/imgres?imgurl=http%3A%2F%2Fscihi.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2014%2F12%2FCicero-619×1024.png&tbnid=7Et1cliwXqmeIM&vet=10CAQQxiAoAmoXChMIwI731KCFgwMVAAAAAB0AAAAAEA0..i&imgrefurl=http%3A%2F%2Fscihi.org%2Fmarcus-tullius-cicero-homo-novus%2F&docid=iBCg84NfCo2gMM&w=619&h=1024&itg=1&q=images%20of%20Cicero&client=firefox-b-1-d&ved=0CAQQxiAoAmoXChMIwI731KCFgwMVAAAAAB0AAAAAEA0>

[5] Cicero. “The Fifth Book of the Second Pleading in the Prosecution against Verres.”

[6] Josephus, Flavius. Wars of the Jews. Book IV, Chapter V. <http://books.google.com/books?id=e0dAAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false>

[7] Tacitus, Gaius Cornelius. The Annals. Ed. Church, Alfred John and Brodribb, William Jackson. <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.02.0078> Perseus Digital Library. Ed. Crane, Gregory R. Tufts University. n.d. Word search “crucified” <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/searchresults?page=4&q=crucified> Suetonious. The Lives of the Twelve Caesars. “The Life of Augustus.” #57, Footnote “e.” <https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Suetonius/12Caesars/Augustus*.html#ref:no_crucifixions_when_Augustus_entered_a_city>

[8] “Seneca.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Ed. Zalta, Edward N. 2015. <https://plato.stanford.edu> Mastin, Luke. “Ancient Rome – Seneca the Younger.” 2009. Classical Literature. <http://www.ancient-literature.com/rome_seneca.html>

[9] Seneca, Lucius Annaeus. “De Consolatione Ad Marciam+.” “To Marcia on Consolation.” Moral Essays. Trans. John W. Basore. 1928-1935. “Seneca’s Essays Volume II.” Book VI. Pages xx 1-3. The Stoic Legacy to the Renaissance. 2004. <http://www.stoics.com/seneca_essays_book_2.html#%E2%80%98MARCIAM1> Seneca, Lucius Annaeus. “De Vita Beata+.” “To Gallio On The Happy Life.” Moral Essays. Trans. John W. Basore. 1928-1935. “Seneca’s Essays Volume II.” Book VII. The Stoic Legacy to the Renaissance. 2004. <http://www.stoics.com/seneca_essays_book_2.html#%E2%80%98BEATA1>

[10] “gibbet.” The Free Dictionary by Farlex. 2022. <https://www.thefreedictionary.com/gibbet>“gibbet.” Merriam-Webster.com. 2022. <https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/gibbet>

[11] “Crucifixion.” JewishEncyclopedia.com. Ciantar, Joe Zammit. Times Malta. “Recollections on Crucifixion – Part one.” image. 2022. <https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/recollections-on-crucifixion-part-one.861097> Champlain, Edward. Nero. Harvard University Press. 2009. <https://books.google.com/books?id=30Wa-l9B5IoC&lpg=PA122&ots=nw4edgV_xw&dq=crucifixion%2C%20tacitus&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false>

[12] “FLORUS, GESSIUS (or, incorrectly, Cestius).” JewishEncyclopedia.com. <http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/6200-florus-gessius>

[13] Josephus, Flavius. Wars of the Jews. Book II, Chapter XIV. <http://books.google.com/books?id=e0dAAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false>

[14] Josephus. Wars. Book V, Chapter XI.