Crucifixion Prophecies of the Messiah

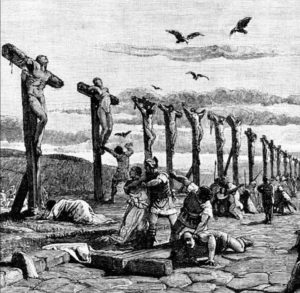

Jesus of Nazareth pointed to prophecies that were to be fulfilled by the Messiah, according to Gospels Mark and Luke, although no one specific prophecy is sited. Jesus told the Disciples, “everything that is written about the Son of Man by the prophets will be accomplished.”[1] Prophecies are seldom as clear as Micah’s Bethlehem prophecy predicting the Ruler of Israel would come from Bethlehem or Zechariah’s prophecy foretelling the King of Israel would come riding on the foal of a donkey.[2] Some are delivered in perplexing, oracle-style prophecies often requiring knowledge of historical context, analogies or symbolisms, and intermingling the present and future.[3] Three parashahs or passages from the Old Testament, the Tenakh, are the focus of potential crucifixion prophecies – Psalms 22:1-24, Isaiah 52:13-53:12 and Zechariah 12:8-14. Historical and modern medical analysis are consistent with them. Historical context substantiating the Gospels first comes from Cicero, Rome’s most celebrated orator and lawyer, describing the details of a crucifixion. In a murder prosecution case, he described how a victim of a Roman crucifixion was first scourged, “exposed to torture and nailed on that cross” – it was “the most miserable and the most painful punishment appropriate to slaves alone.”[4] Jewish historian Josephus additionally wrote in several accounts about the terrors of crucifixion and how it became a commonplace means to kill Jews, convicted or innocent. Rescued victims from the cross did not even survive the attempted crucifixions as attested by his own personal experience.[5]

Judaism and Christianity have disagreements on the exact meaning of Messiah prophecies, even within their own ranks. One exception; however, they virtually all agree on one aspect in the Zechariah 12:10 prophecy.

Succinctly, the prophecy foretells the Messiah will be killed and “… they will mourn for him as one mourns for an only child, and grieve bitterly for him as one grieves for a firstborn son.” Christianity points to the Gospel accounts that describe Jesus being pierced by nails and thrust with a spear.[6]

A potential Psalms prophecy of a death by crucifixion is the well-known yet controversial, Psalms 22, depicting a man whose “bones [are] out of joint,” “heart has turned to wax,” “tongue sticks to the roof of my mouth,” and “they have pierced my hands and feet.” Psalm 22 also describes the psychological torture of enduring agony, humiliation, taunting and insults.[7]

Modern forensic medical expert analysis of a crucifixion provides further context. The act of merely trying to take a breath added to the excruciating pain of being nailed to a cross by pulling at the nail wounds driven through nerves in the wrists while pushing up full body weight on nailed feet. Many of the crucifixion victims most likely died by asphyxiation.[8]

Isaiah’s 52-53 parashah is a graphic depiction wholly consistent with that of a Roman crucifixion. Further details in the passage describe how “My Servant” will be treated.

Virtually all Bibles for Isaiah 53:5 contains the word chalal, one of those words that have multiple definitions. Two main definitions categories are either a form meaning “to profane, defile, pollute, desecrate” or “to wound (fatally), bore through, pierce, bore.”

Christian Bibles, in about a 50/50 split, translate chalal as either “pierced” or “wounded.” Jewish Bibles likewise interpret chalal differently with the Jewish Publication Society and the William Davidson translations use “wounded” while The Complete Jewish Bible uses the word “pained.

“My Servant” is depicted to have a physical “appearance was so disfigured beyond that of any man and his form marred beyond human likeness.” Described next, the mental anguish of suffering of his soul,” is “despised and rejected by men” and is considered “stricken by God, smitten by him, and afflicted.”[9]

Jewish authorities are virtually silent on the parashah as a whole being a prophecy about the Messiah yet 6 of the 15 verses – 52:13, 15, 53:2, 3, 5, 7 – are considered by various Jewish authorities to be prophecies about the Messiah.[10] Talmud tractate Sanhedrin 98b quotes Isaiah 53:3 as the prophetic basis for one of the names of the Messiah.[11]

Independently of his contributions to the Talmud, Jose the Galilean wrote the Messiah would be wounded for our transgressions quoting from Isaiah 53.7.[12] He quoted Isaiah 53:5 declaring it is a prophecy referring to “King Messiah” who would be “wounded” for our transgressions.

Rabbi Maimonides similarly identified the Messiah as the subject of Isaiah 52:15 and 53:2. The Rabbi sage expounded the Messiah could be identified by his origins and his wonders.

Rabbi Moshe Kohen ibn Crispin boldly disagreed with the prevailing Jewish view that “My Servant” is a metaphor referring to the nation of Israel, rather “My Servant” in Isaiah 52:13 refers to “King Messiah.”[13]12 Crispin is renowned for his twelfth century authorship of Sefer ha-Musar meaning the Book of Instruction.

Days before entering Jerusalem for the last time, Jesus forewarned his Disciples predicting what he was about to endure as foretold by the prophets:

Jewish historian Josephus additionally wrote in several accounts about the terrors of crucifixion and how it became a commonplace means to kill Jews, convicted or innocent. Rescued victims from the cross did not even survive the attempted crucifixions as attested by his own personal experience.[5]

Judaism and Christianity have disagreements on the exact meaning of Messiah prophecies, even within their own ranks. One exception; however, they virtually all agree on one aspect in the Zechariah 12:10 prophecy.

Succinctly, the prophecy foretells the Messiah will be killed and “… they will mourn for him as one mourns for an only child, and grieve bitterly for him as one grieves for a firstborn son.” Christianity points to the Gospel accounts that describe Jesus being pierced by nails and thrust with a spear.[6]

A potential Psalms prophecy of a death by crucifixion is the well-known yet controversial, Psalms 22, depicting a man whose “bones [are] out of joint,” “heart has turned to wax,” “tongue sticks to the roof of my mouth,” and “they have pierced my hands and feet.” Psalm 22 also describes the psychological torture of enduring agony, humiliation, taunting and insults.[7]

Modern forensic medical expert analysis of a crucifixion provides further context. The act of merely trying to take a breath added to the excruciating pain of being nailed to a cross by pulling at the nail wounds driven through nerves in the wrists while pushing up full body weight on nailed feet. Many of the crucifixion victims most likely died by asphyxiation.[8]

Isaiah’s 52-53 parashah is a graphic depiction wholly consistent with that of a Roman crucifixion. Further details in the passage describe how “My Servant” will be treated.

Virtually all Bibles for Isaiah 53:5 contains the word chalal, one of those words that have multiple definitions. Two main definitions categories are either a form meaning “to profane, defile, pollute, desecrate” or “to wound (fatally), bore through, pierce, bore.”

Christian Bibles, in about a 50/50 split, translate chalal as either “pierced” or “wounded.” Jewish Bibles likewise interpret chalal differently with the Jewish Publication Society and the William Davidson translations use “wounded” while The Complete Jewish Bible uses the word “pained.

“My Servant” is depicted to have a physical “appearance was so disfigured beyond that of any man and his form marred beyond human likeness.” Described next, the mental anguish of suffering of his soul,” is “despised and rejected by men” and is considered “stricken by God, smitten by him, and afflicted.”[9]

Jewish authorities are virtually silent on the parashah as a whole being a prophecy about the Messiah yet 6 of the 15 verses – 52:13, 15, 53:2, 3, 5, 7 – are considered by various Jewish authorities to be prophecies about the Messiah.[10] Talmud tractate Sanhedrin 98b quotes Isaiah 53:3 as the prophetic basis for one of the names of the Messiah.[11]

Independently of his contributions to the Talmud, Jose the Galilean wrote the Messiah would be wounded for our transgressions quoting from Isaiah 53.7.[12] He quoted Isaiah 53:5 declaring it is a prophecy referring to “King Messiah” who would be “wounded” for our transgressions.

Rabbi Maimonides similarly identified the Messiah as the subject of Isaiah 52:15 and 53:2. The Rabbi sage expounded the Messiah could be identified by his origins and his wonders.

Rabbi Moshe Kohen ibn Crispin boldly disagreed with the prevailing Jewish view that “My Servant” is a metaphor referring to the nation of Israel, rather “My Servant” in Isaiah 52:13 refers to “King Messiah.”[13]12 Crispin is renowned for his twelfth century authorship of Sefer ha-Musar meaning the Book of Instruction.

Days before entering Jerusalem for the last time, Jesus forewarned his Disciples predicting what he was about to endure as foretold by the prophets:

LK 18:31-32 “Jesus took the Twelve aside and told them, “We are going up to Jerusalem, and everything that is written by the prophets about the Son of Man will be fulfilled. He will be turned over to the Gentiles. They will mock him, insult him, spit on him, flog him and kill him.”(NIV)

History, Judaism and Christainity affirm that Jesus of Nazareth was subjected to the horrific physical and psychological designs of a crucifixion consistent with accounts of historians and modern forensic science analysis. Is crucifixion predicted in the Messiah prophecies foretelling the manner of suffering and death by the Messiah? Rabbi Crispin profoundly summed up the challenge for each person to arrive at his or her own conclusion about the prophecies:“… if any one should arise claiming to be himself the Messiah, we may reflect, and look to see whether we can observe in him any resemblance to the traits described here: if there is any such resemblance, then we may believe that he is the Messiah our righteousness; but if not, we cannot do so.”[14] – Rabbi Crispin

Updated February 12, 2024.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

REFERENCES:

[1] Like 18:31. NASB. Luke 18:31-34;24:26. CR Mark 18:31, 1931; Luke 22:37. [2] Micah 5:2; Zechariah 9:9. [3] Psalms 78:1-3; Hosea 12:10. Boucher, Madeleine I. “The Parables.” Excerpt from The Parables. Washington, DE: Michael Glazier, Inc. 1980. PBS|Frontline. n.d. <http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/religion/jesus/parables.html> Bugg, Michael. “Types of Prophecy and Prophetic Types.” Hebrew Root. n.d. <http://www.hebrewroot.com/Articles/prophetic_types.htm> [4] Cicero, Marcus Tullius. In Verrem Actionis Secundae M. Tulli Ciceronis Libri Quinti. “Secondary Orations Against Verres. Book 5, LXVI. 70 B.C. The Society for Ancient Languages University of Alabama – Huntsville. 10 Feb. 2005. <https://web.archive.org/web/20160430183826/http://www.uah.edu/student_life/organizations/SAL/texts/latin/classical/cicero/inverrems5e.html> Quintilian, Marcus Fabius. Quintilian’s Institutes of Oratory. 1856. Trans. John Selby Watson. Book 8, Chapter 4. <https://web.archive.org/web/20170815223340/http://rhetoric.eserver.org/quintilian/index.html> [5] Josephus, Flavius. Wars of the Jews. Book II, Chapter XIV. Book V, Chapter XI. <http://books.google.com/books?id=e0dAAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false> Chkoreff, Larry. International School of The Bible. “Is There a New World Coming?” crucifixion. image. 2000. <http://www.isob-bible.org/world-new/04world_files/image019.gif> [6] The Compete Jewish Bible – with Rashi Commentary. Zechariah 12:10 <http://www.chabad.org/library/bible_cdo/aid/63255/jewish/The-Bible-with-Rashi.htm> Soncino Babylonian Talmud. Sukkah 52a. <http://www.halakhah.com/rst/moed/16b%20-%20Succah%20-%2029b-56b.pdf> Chkoreff, Larry. International School of The Bible. “Is There a New World Coming?” crucifixion. image. 2000. <http://www.isob-bible.org/world-new/04world_files/image019.gif> [7] Cilliers, L. & Retief F. P. “The history and pathology of crucifixion.” South African Medical Journal. Dec;93(12):938-41. U.S. National Library of Medicine|National Institute of Health. <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14750495> Zugibe, Frederick T. “Turin Lecture: Forensic and Clinical Knowledge of the Practice of Crucifixion.” E-Forensic Medicine. 2005. <http://web.archive.org/web/20130925103021/http:/e-forensicmedicine.net/Turin2000.htm> Maslen, Matthew W. and Mitchell, Piers D. “Medical theories on the cause of death in crucifixion.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. J R Soc Med. 2006 April; 99(4): 185–188. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.99.4.185. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Search term Search database. <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1420788> Alchin, Linda. “Roman Crucifixion.” Tribunes and Triumphs. 2008. <http://www.tribunesandtriumphs.org/roman-life/roman-crucifixion.htm> Zias, Joe. “Crucifixion in Antiquity – The Anthropological Evidence.” JoeZias.com. 2009. <http://web.archive.org/web/20121211060740/http://www.joezias.com/CrucifixionAntiquity.html> Champlain, Edward. Nero. 2009. <https://books.google.com/books?id=30Wa-l9B5IoC&lpg=PA122&ots=nw4edgV_xw&dq=crucifixion%2C%20tacitus&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false> [8] The Complete Jewish Bible – with Rashi Commentary. <http://www.chabad.org/library/bible_cdo/aid/63255/jewish/The-Bible-with-Rashi.htm> Jewish Publication Society (JPS) translation. 1917. Benyamin Pilant. 1997. <http://www.breslov.com/bible> William Davidson Talmud, The. Talmud Bavli. The Sefaria Library. <http://www.sefaria.org/texts/Talmud> Isaiah 53:5. NetBible. Hebrew text. <https://classic.net.bible.org/verse.php?book=Isa&chapter=53&verse=5> Chalal <02490> NetBible. definitions. <https://classic.net.bible.org/strong.php?id=02490> H2490. Lexicon-Concordance Online Bible. n.d. <http://lexiconcordance.com/hebrew/2490.html> Isaiah 53:5. BibleHub. 2022. <https://biblehub.com/lexicon/isaiah/53-5.htm > <https://biblehub.com/lexicon/isaiah/53-5.htm > <https://biblehub.com/isaiah/53-5.htm> [9] Isaiah 53:3. Soncino Babylonian Talmud. Sanhedrin 98a. Soncino Babylonian Talmud. footnotes: Isaiah XLIX:7, XVIII:5, I:25, LIX:19, LIX:20, LX:21, LIX:16, XLVIII:11, LX:22; footnote #31. <https://israelect.com/Come-and-Hear/sanhedrin/sanhedrin_98.html> Soncino Babylonian Talmud. Sanhedrin 38a, footnote #9 to Isaiah 8:14. <https://israelect.com/Come-and-Hear/sanhedrin/sanhedrin_38.html> [10] Sanhedrin 98a footnotes: Isaiah XLIX:7, XVIII:5, I:25, LIX:19, LIX:20, LX:21, LIX:16, XLVIII:11, LX:22; footnote #31. <https://israelect.com/Come-and-Hear/sanhedrin/sanhedrin_98.html> Soncino Babylonian Talmud. Sanhedrin 38a, footnote #9 to Isaiah 8:14. <https://israelect.com/Come-and-Hear/sanhedrin/sanhedrin_38.html> [11] Moses Maimonides. Neubauer, Adolf. And Driver, Samuel Rolles. The Fifty-third Chapter of Isaiah According to the Jewish Interpreters. 1877. “Letter to the South (Yemen).” pp xvi, 374-375. <http://books.google.com/books?id=YxdbAAAAQAAJ&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q=advent&f=false> Isaiah 53:3. Soncino Babylonian Talmud. Ed. Isidore Epstein. Sanhedrin 98b, footnote #31. <https://israelect.com/Come-and-Hear/talmud/index.html> CR Neubauer, Driver & Rolles. The Fifty-third Chapter of Isaiah According to the Jewish Interpreters. pp 12-16. [12] The Babylonian Talmud. Rodkinson. “Part I. Historical and Literary Introduction to the New Edition of the Talmud, Chapter 2.” pp 10, 12-13. <http://www.sacred-texts.com/jud/t10/ht202.htm> The Babylonian Talmud. Derech Eretz-Zuta. “The Chapter on Peace.” Yose the Galilaean. Neubauer, Driver & Rolles. The Fifty-third Chapter of Isaiah According to the Jewish Interpreters. Quote. Siphrej. pp 10-16. <https://books.google.com/books?id=YxdbAAAAQAAJ&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q=Jose&f=false> [13] Crispin, Moshe Kohen ibn. Neubauer, Driver & Rolles. The Fifty-third Chapter of Isaiah According to the Jewish Interpreters “Sefer ha-Musar.” pp 99-101. [14] Crispin. “Sefer ha-Musar.” p 114.

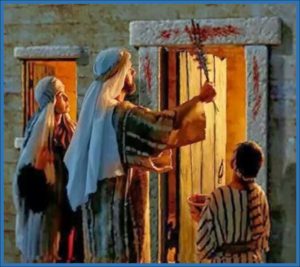

Leading up to the horrible night of the 10th plague, God offered protection for the Hebrews if they followed a precise sacrificial ritual. Each family was to choose one of their unblemished lambs, sacrifice it, splash its blood on the door posts of their homes, and roast the lamb for a family feast at sunset.

Leading up to the horrible night of the 10th plague, God offered protection for the Hebrews if they followed a precise sacrificial ritual. Each family was to choose one of their unblemished lambs, sacrifice it, splash its blood on the door posts of their homes, and roast the lamb for a family feast at sunset.