Psalms 22 Controversy – Science & the Translation

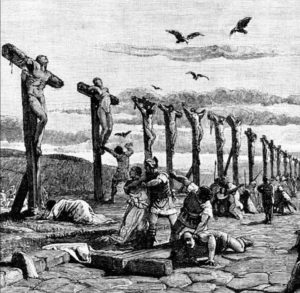

One key verse of Psalms 22 creates a two-part controversy starting first with its translation difference between Christian and Jewish Bibles. That difference then leads to the next controversy, whether Psalms 22 is a foreshadowing or prophecy that foretells the crucifixion death of the Messiah.[1]

Christian Bibles translations vary, yet are consistent with the New King James Version of Psalms 22:16. Appearing one verse later in Psalms 22:17 in Jewish Bibles, the Complete Jewish Bible translation generally agrees with other Jewish Bibles, although with some further translation variations. Overall, the translation differences between the Jewish and Christian Bibles are significant:

“Dogs have surrounded me; a band of evil men has encircled me, they have pierced my hands and my feet. (NJKV)

“For dogs have surrounded me; a band of evildoers has encompassed me, like a lion, my hands and feet.(CJB)

One tiny detail is the point of contention – the single character of one Hebrew word completely changes its meaning. In digital text, the difference is visually somewhat easy to see:

כארי

vs.

כארו

Handwritten on an ancient scroll, the difference is almost indistinguishable to the untrained eye without magnifcation.[2] Taking special care not to miss such distinctions was even a challenge for the Rabbi authors of the Talmud:

“R. Awira…as it is written [Prov. xxv. 21]: “If thy enemy be hungry, give him bread to eat, and if he be thirsty, give him water to drink; for though thou gatherest coals of fire upon his head, yet will the Lord repay it unto thee.” Do not read שלם (repay it), but שלים (he will make him peaceful toward thee).”

In Hebrew text, the slightest spelling variation can alter the entire meaning of a sentence, even changing a noun to a verb.[4] It is important to remember that Hebrew is written and read from right to left. In the case of Psalms 22:16/17, the impact on the translation is striking.

Jewish Bibles mostly translate the Hebrew word כארי (K’ari / Ka’ari) as “like a lion my hands and feet” with some translations reading “like lions [they maul] my hands and feet;” others “like a lion they are at my hands and my feet.”[5] All are meaningfully different from Christian Bibles based on the Hebrew word כארו (K’aru / Ka’aru) translated as “they have dug,” “pierced” or “pin.”[6]

Digging deeper, the root of the controversy lies with the age of the ancient Hebrew text source.[7] One Biblical text is over a millennium older than the other.

Septuagint LXX is the Hebrew-to-Greek standard translation dating to the period of 285-247 BC. According to Josephus, at the behest of Ptolemy Philadelphius, ruler of Egypt, the Hebrew-to-Greek is translated directly from Hebrew scrolls borrowed from the Temple. The translation was performed by 72 Jewish scholars, 6 from each tribe, hence the Roman numeral “LXX”.[8]

Each Jewish translator was independently secluded until the end of the project. At the conclusion, the combined translation was presented for approval to all the Jewish priests, elders and the principal men of the commonwealth. Once approved, King Ptolemy ordered the finalized official translation to remain “uncorrupted.”

Jewish Bibles are based on two surviving Hebrew Masoretic texts (MT), the Aleppo Codex dated to 925 AD and the Hebrew Leningrad Codex c. 1008-10 AD, over millennium after the Septuagint.[9] About a third of the Aleppo text has been missing since 1947 when a riot broke out in Aleppo, Syria, and the Synagogue holding the text was set ablaze.[10]

Modern Hebrew translations now have a dependency on the more recent Leningrad manuscript to fill in the missing content.[11] According to Menachem Cohen, Professor of Bible at Bar-Ilan University of Israel and director of the Miqraot Gedolot HaKeter Project, the Masoretic Text (MT) is the culmination of many variations of textual sources, spelling changes, and interpretations compiled into a final text.

Cohen stated that unlike the Septuagint, the MT lacked the benefit of a side-by-side comparison to the original “witnessing” Hebrew text. The Professor explained it this way: [12]

“…the aggregate of known differences in the Greek translations is enough to rule out the possibility that we have before us today’s Masoretic Text. The same can be said of the various Aramaic translations; the differences they reflect are too numerous for us to class their vorlage [original text] as our Masoretic Text.”

Using the science of textual criticism, Professor Cohen’s project team explained how the Masoretic text diverged from the 1250-year older Septuagint translation. The changes began at some point before the Roman’s destruction of the Jewish Temple in 70 AD:[13]

“In any case, it seems that after the destruction the array of text-types disappeared from normative Judaism, and the Masoretic type alone remained.”

“During the same period, new Greek translations were being prepared in place of the Septuagint, which, by virtue of its becoming an official Christian text, was rejected by the Jews. These translations, especially that of Aqilas which was praised by the Sages, reflected the Masoretic text-type.[14]

A potentially game-changing scroll discovery was made in the 1950s at the Bar Kochba archeological site. A Jewish rebellion against Rome from 132-135 AD, called the Bar-Kokhba revolt, was led by Simon ben Kochba, a rebel Jewish leader and military commander known for his strict adherence to traditional Jewish law.[15] Professor Cohen remarked:

“In the fifties, remnants of Scriptural scrolls used by Bar Kochba’s soldiers were found in the Judean desert (Wadi Murabba’at and Nahal Hever). They all show that Bar Kochba’s people used the same text which we call the MT, with only the slightest of differences.”

Nahal (Nachal) Hever scrolls, as they are now called, are dated to the years between 2 BC – 68 AD predating the Leningrad Codex MT by about 1000 years, still some 200-300 years after the Septuagint LXX translation. Essentially coinciding with the lifetime of Jesus of Nazareth, the dating of these scrolls serve to dispel the charge of Christian manipulation of the Septuagint text to fit the Gospels written after the crucifixion of Jesus.[16]

One of the Nahal Hever scrolls surviving relatively intact is Psalms 22. The potentially game-changing text uses the Hebrew word כארו (K’aru).[17] A translation of the Nehal Hever scroll from Psalms 22:14-18 by Dr. Martin Abegg Jr., Dr. Peter Flint and Eugene Ulrich reads:[18]

“[I have] been poured out [like water, and all] my bon[es are out of joint. My heart has turned to wax; it has mel]ted away in my breast. [My strength is dried up like a potsherd], and my tongue melts in [my mouth. They] have placed [me] as the dust of death. [For] dogs are [all around me]; a gang of evil[doers] encircles me. They have pierced my hands and feet. [I can count all my bones; people stare and gloat over me. They divide my garments among themselves and they cast lots for my] clothes.” * [19]

Archeological discovery and textual analysis of the Nahal Hever scrolls corroborate the much older Septuagint text translation of Psalms 22:16(17), both bearing the Hebrew word כארו (K’aru), “they have dug,” “pierced” or “pin.” Do these two text discoveries strengthen the view that Psalms 22:14-18 is a foreshadowing or prophecy of the Messiah’s manner of death?

* The words appearing in brackets were missing from the manuscript and have been supplied from other texts, if available. The words appearing in italics are those that differ from the later Masoretic text.

Updated November 4, 2023.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

REFERENCES:

[1] Davidson, Paul. “A Few Remarks on the Problem of Psalm 22:16.” Is That in the Bible? 2015. <https://isthatinthebible.wordpress.com/2015/09/28/a-few-remarks-on-the-problem-of-psalm-2216> “Psalm 22.” Heart of Israel. n.d. <http://www.heartofisrael.net/chazak/articles/ps22.htm> <http://web.archive.org/web/20171016070503/http://www.heartofisrael.net/chazak/articles/ps22.htm> Barrett, Ruben. “Bible Q&A: Psalms 22.” HaDavar Ministries. 27 May 2008. Archived URL. Archive.org. 23 Aug. 2012. <http://web.archive.org/web/20120823025747/http://www.hadavar.net/articles/45-biblequestionsanswers/54-psalm22questions.html>

[2] Hegg, Tim. “Studies in the Biblical Text – Psalm 22:16 – “like a lion” or “they pierced”?” Torah Resource. 2013. <https://www.torahresource.com/EnglishArticles/Ps22.16.pdf>

[3] The Babylonian Talmud. Rodkinson. Book 4: Tracts Pesachim, Yomah and Hagiga, Chapter V. Psalms 22 Hebrew Text fragment. BibleHumanities.org. image. 2012.http://bhebrew.biblicalhumanities.org/viewtopic.php?t=22288>

[4] Fox, Tsivya. “Aleph, the First Hebrew Letter, Contains Depths of Godly Implications.” August 30, 2016. <https://www.breakingisraelnews.com/74824/adding-aleph-helps-bring-redemption> Benner, Jeff A. “Introduction to Ancient Hebrew.” Ancient Hebrew Research Center. 2019. <https://www.ancient-hebrew.org/introduction.htm> Benner, Jeff, The Ancient Hebrew Alphabet. 2019. <https://www.ancient-hebrew.org/introduction.htm> Benner, Jeff A. “The Ancient Pictographic Alphabet.” Ancient Hebrew Research Center. 2019. <http://www.ancient-hebrew.org/6_02.html> Benner, Jeff A. “Parent Roots of Hebrew Words.” Ancient Hebrew Research Center. 2019. <https://www.ancient-hebrew.org/introduction.htm> Benner, Jeff A. “Anatomy of Hebrew Words.” Ancient Hebrew Research Center. 2019. <http://www.ancient-hebrew.org/vocabulary_anatomy.html> “Punctuation.” Jewish Encyclopedia. 2011. <http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/12441-punctuation> Miller, Fred P. Moellerhaus Publishers. “Pluses and Minuses Caused by a Different Vorlage.” n.d. <http://www.moellerhaus.com/vorlage.html>

[5] “Psalms 22.” The Compete Jewish Bible – with Rashi Commentary. <https://www.chabad.org/library/bible_cdo/aid/16243> “TEHILIM (Book of Psalms) Chapter 22.” Jewish Publication Society (JPS) translation. 1917. <http://www.breslov.com/bible/Psalms22.htm#17> “Psalms 22.” Sefaria. <https://www.sefaria.org/Psalms.22?lang=bi>

[6] Bible Hub. “Psalms 22.” 2018. <https://biblehub.com/psalms/22-1.htm> Bible.org. “Psalms 22.” 2019. <http://classic.net.bible.org/bible.php?book=Psa&chapter=22>

[7] “Psalm 22.” MessianicArt.com. 2004.<http://web.archive.org/web/20120627010236/http://messianicart.com/chazak/yeshua/psalm22.htm> “Psalms 22 Questions and Comments.” JewishRoots.net. 2014. <http://jewishroots.net/library/prophecy/psalms/psalm-22/psalm-22-comments-from-hadavar-ministries.html> “”They pierced my hands and my feet” or “Like a lion my hands and my feet” in Psalm 22:16?” KJV Today. n.d. http://kjvtoday.com/home/they-pierced-my-hands-and-my-feet-or-like-a-lion-my-hands-and-my-feet-in-psalm-2216> Delitzsch, Franz. The Psalms.1880. pp 42-43, 317-320.<http://archive.org/stream/commentarypsalm01deliuoft#page/n9/mode/2up> Benner, Jeff A. “Psalm 22:17 – “Like a lion” or “they pierced?”.” 2018. <https://www.patreon.com/posts/psalm-22-17-like-22030018>

[8] Josephus, Flavius. Antiquities of the Jews. Book XII, Chapter II.1-6. Trans. and commentary William Whitson. The Complete Works of Josephus. 1850. <http://books.google.com/books?id=e0dAAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false> “The Septuagint (LXX).” Ecclesiastic Commonwealth Community. n.d. <http://ecclesia.org/truth/septuagint.html> “Septuagint.” Septuagint.Net. 2018. <http://septuagint.net> “Septuagint.” Encyclopædia Britannica. 2019. <https://www.britannica.com/topic/Septuagint>

[9] Lundberg, Marilyn J. “The Leningrad Codex.” USC West Semitic Research Project. 2012. University of Southern California. 8 Jan. 1999. <https://web.archive.org/web/20170403025034/http://www.usc.edu/dept/LAS/wsrp/educational_site/biblical_manuscripts/LeningradCodex.shtml> Abegg, Jr., Martin G., Flint, Peter W. and Ulrich Eugene Charles. The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible: the oldest known Bible translated for the first time into English. “Introduction”, page x. (page hidden by Google Books). 2002. <https://books.google.com/books?id=c4R9c7wAurQC&lpg=PP1&ots=fQpCpzCdb5&dq=Abegg%2C%20Flint%20and%20Ulrich2C%20The%20Dead%20Dead%20Sea%20Scrolls%20Bible%2C&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q=Isaiah&f=false> Aronson, Ya’akov. “Mikraot Gedolot haKeter–Biblia Rabbinica: Behind the scenes with the project team.” Association Jewish Libraries. Bar Ilan University. Ramat Gan, Israel. n.d. No longer available free online – available for purchase: <http://www.biupress.co.il/website_en/index.asp?category=12&id=714>

[10] Ben-David, Lenny. “Aleppo, Syria 100 Years Ago – and Today.” 23/07/15. Arutz Sheva 7 | isralenationalnews.com. <http://www.israelnationalnews.com/News/News.aspx/198521> Ofer, Yosef. “The Aleppo Codex.” n.d. <http://www.aleppocodex.org/links/6.html> Bergman, Ronen. “A High Holy Whodunit.” New York Times Magazine. July 25, 2012. <https://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/29/magazine/the-aleppo-codex-mystery.html>

[11] Leviant, Curt. Jewish Virtual Library. 2019. “Jewish Holy Scriptures: The Leningrad Codex.” <https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-leningrad-codex> “Leningrad Codex.” Bible Manuscript Society. 2019. <https://biblemanuscriptsociety.com/Bible-resources/Bible-manuscripts/Leningrad-Codex>

[12] Cohen, Menachem. “The Idea of the Sanctity of the Biblical Text and the Science of Textual Criticism.” Eds. Uriel Simon and Isaac B Gottlieb. 1979. Australian National University. College of Engineering & Computer Science. <http://cs.anu.edu.au/%7Ebdm/dilugim/CohenArt> Miller, Fred P. Moellerhaus Publishers. “Pluses and Minuses Caused by a Different Vorlage.” n.d. <http://www.moellerhaus.com/vorlage.html>

[13] “Siege of Jerusalem.” Encyclopædia Britannica. 2019. <https://www.britannica.com/event/Siege-of-Jerusalem-70>

[15] “Shimon Bar-Kokhba (c. 15 – 135).” Jewish Virtual Library. 2019. <https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/shimon-bar-kokhba> “Bar Kochba.” Livius.org. Ed. Jona Lendering. 2019.< https://www.livius.org/articles/concept/roman-jewish-wars/roman-jewish-wars-8/>

[16] “Psalm 22.” Heart of Israel.

[17] Hegg. “Studies in the Biblical Text – Psalm 22:16 – “like a lion” or “they pierced”?”

[18] Abegg, et. al. The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible. p xiv (hidden by Google Books).

[19] Abegg, et. al. The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible. p 518. (hidden by Google Books).

Jewish historian

Jewish historian