Are the Gospels in Sync with the Passover?

Interwoven throughout the Gospels are 21 references to the Passover by name and 6 references to either “the feast” or “the festival.” Skeptics make the charge that the Gospels contain Passover observance contradictions.[1]

Interwoven throughout the Gospels are 21 references to the Passover by name and 6 references to either “the feast” or “the festival.” Skeptics make the charge that the Gospels contain Passover observance contradictions.[1]

Final days of Jesus of Nazareth took place during the annual Passover observance in Jerusalem. Circumstances surrounding the Passover in his case are the trial, execution and Resurrection.

Passover began when Moses defied Pharaoh in Egypt ending with the 10th plague, death of the firstborn.[2] Hebrews were spared when the angel of death passed over their homes bearing the blood of the sacrificial lambs over their doorposts.

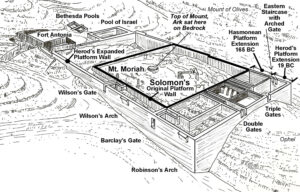

God declared at Mount Sinai that this act of salvation was to be observed annually by the Hebrews to “sacrifice the Passover to the LORD your God” in the place where the LORD chooses to establish His name.”[3] Yet to be revealed was the location of the place.

At the onset of Nissan 15, the Feast of Unleavened Bread was to be eaten.[4] A key distinction, Jewish days begin at twilight just after sunset.[5]

Passover began at twilight of Nissan 14 just after the Pascal Lamb had been sacrificed earlier that afternoon. Strict requirements for the Passover appear in the books of the Law of Moses – Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy.[6]

Sunrise brought the initial daylight hours of the first day of Passover, Nissan 15, along with the daily necessities still to come. People were busy with required and traditional activities including meals and more sacrifices

Roasted lamb from the Pascal sacrifice became the main course of the Feast of Unleavened Bread.[7] The sacrifice meat was intended to feed 10 to 20 people for a festive and joyous occasion to celebrate God’s deliverance from bondage – freedom.

Jewish Talmudic law defined the sacrifices for each day including the meal plan for the first day of Passover. An entire tractate in the Babylonia Talmud entitled Chagigah is devoted to addressing the various expectations and requirements. Two “chagigah sacrifices” were associated with the Passover.[8]

As an optional festal offering, the first chagigah sacrifice was to be offered on Nissan 14 intended to supplement the Paschal sacrifice ensuring there would be enough meat to feed a large Passover company. It was equal to the paschal sacrifice itself and expected to provide for enjoyment of the festival.

Sacrificed first, there was to be no interruption with the Pascal Lamb sacrifice and the Feast of Unleavened Bread. Likewise, both had to be consumed by midnight with any leftovers from the meal to be burned.[9]

Called exactly that, the Chagigah, it had a different purpose and rules than the first optional chagigah sacrifice. It was an obligatory, private “peace offering” to be offered by an individual at the Temple with the assistance of a Priest who became a beneficiary to it.

A portion of this second chagigah sacrifice on Nisan 15 of Passover was to be given to God, a portion to the Priest as a tithe for his own meal, and the remaining portion of meat was to be taken home by the offerer for his own Chagigah meal. For this reason, a priest had a vested personal interest to assist in the sacrifice.

Meat from this second chagigah sacrifice was to be served as the main course before evening of the first day of Passover. The meal was to be consumed over the course of two days and one night – the first and second days of Passover, Nissan 15 and 16, and the night in between.

Things get interesting as it relates to the Gospels’ accounts describing the final hours in the life of Jesus of Nazareth, especially John 18:28. Two references are the cause of contention – the meal and the defilement.

JN 18:28 “They did not go into the governor’s residence so they would not be ceremonially defiled, but could eat the Passover meal.”(NET)

The Feast of Unleavened Bread had been eaten, Jesus was later arrested that evening and put on trial during the night. Early that same morning of Nisan 15, Jesus was taken by the Jewish leadership to Pilate at the Praetorium where the priests refused to go inside.

Entering the Praetorium was one of those things that could place a priest in a state of ritual defilement. When the author added “so they would not be defiled,” this could only be referring to the second Passover chigigiah meal since it was after the Feast of Unleavened Bread.

John does not explain the reason for the defilement. One possibility is the Jewish legal concept known as touching a dead body or home that once contained a dead body (the presumption was that it was common practice for mourning Romans to display a dead body in a building).[10]

After sunset, a ritualistic purification bath by the priest before the Feast of Unleavened Bread would have absolved this type of ritual defilement that may have occurred day on Nisan 14. In this case, however, it would be too late to absolve a ritual defilement.

A defiled priest on Nisan 15 could not perform any sacrifice that day. As a consequence, he would not receive his lawful portion of the chagigah sacrificial meat for his own meal.

Are the Gospel references to the Passover during the final days in the life of Jesus of Nazareth in agreement with Jewish Law defined in the Old Testament, the Tenakh, and the Talmud?

June 30, 2025.

![]()

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

REFERENCES:

[1] Wells, Steve. <u>The Skeptic’s Annotated Bible</u>. 2017. “423. When was Jesus crucified? <http://skepticsannotatedbible.com/contra/passover_meal.html> “101 Bible Contradictions.” Islamic Awareness. n.d. Contradiction #69. <https://www.islamawareness.net/Christianity/bible_contra_101.html> “Passover.” SVGmall.com. image. n.d. <https://svgmall.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Passover-PNG-Free-Download.jpg?v=1619147248>

[2] Exodus 8-12. Roth, Don. “What year was the first Passover?” Biblical Calendar Proof. 2019. <http://www.biblicalcalendarproof.com/Timeline/PassoverDate>

[3] Deuteronomy 16. NASB.

[4] Exodus 12; Leviticus 23; Numbers 9; Deuteronomy 16. Edersheim, Alfred. The Temple – Its Ministry and Services. 1826-1889. “The Roasting of the Lamb.” pp 67 – 67, 75. <http://www.ntslibrary.com/PDF%20Books/The%20Temple%20

[5] Edersheim. The Temple – Its Ministry and Services. p 65.

[6] Exodus 12; Leviticus 23; Numbers 9; Deuteronomy 16. <http://www.ntslibrary.com/PDF%20Books/The%20Temple%20by%20Alfred%20Edersheim.pdf>

by%20Alfred%20Edersheim.pdf>

[7] Deuteronomy 16. Edersheim, Alfred. The Temple – Its Ministry and Services. “The Roasting of the Lamb.” p 75.

[8] Talmud Bavli. Sefaria. Trans. William Davidson. n.d. <https://www.sefaria.org/texts/Talmud>Edersheim. The Temple – Its Ministry and Services. “The Three Things.” pp 70-71.

[9] Gill. John Gill’s Exposition of the Whole Bible. John; chapters 18-19 commentary. <https://www.studylight.org/commentaries/geb/john-18.html> Edersheim. The Temple – Its Ministry and Services. pp 70-71, 76, 79, 81-82. Josephus, Flavius. Wars of the Jews. Trans. and commentary William Whitson. The Complete Works of Josephus.1850. Book VI, Chapter IX.3. <https://books.google.com/books?id=e0dAAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false> Edersheim, Alfred. The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah. 1883. p 1324. <http://www.ntslibrary.com/PDF%20Books/The%20Life%20and%20Times%20of%20Jesus%20the%20Messiah.pdf>

[10] Leviticus 3, Numbers 19:13. Edersheim, Alfred. The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah. 1883. Philologos Edition: Apr1301. n.d. <http://philologos.org/__eb-lat/default.htm> =The NTSLibrary. 2016. <http://www.ntslibrary.com/PDF%20Books/The%20Life%20and%20Times%20of%20Jesus%20the%20Messiah.pdf>. pp. 1334, 1352, 1394. Edersheim. The Temple – Its Ministry and Services. pp 70-71, 114. The Babylonian Talmud. Rodkinson. Tract Pesachim, Book 3, Chapter VI. <http://www.sacred-texts.com/jud/t03/psc09.htm> Edersheim, Alfred. The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah. p 1324. Gill. John Gill’s Exposition of the Whole Bible. John chapters 18 & 19 commentary.

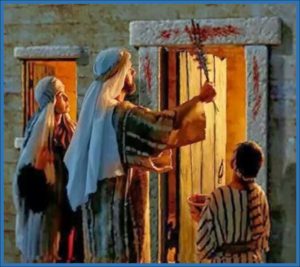

Leading up to the horrible night of the 10th plague, God offered protection for the Hebrews if they followed a precise sacrificial ritual. Each family was to choose one of their unblemished lambs, sacrifice it, splash its blood on the door posts of their homes, and roast the lamb for a family feast at sunset.

Leading up to the horrible night of the 10th plague, God offered protection for the Hebrews if they followed a precise sacrificial ritual. Each family was to choose one of their unblemished lambs, sacrifice it, splash its blood on the door posts of their homes, and roast the lamb for a family feast at sunset.